Chinese Time Expressions: How to Express Time and Duration in Mandarin

Last updated: January 28, 2026

Talking about time when learning Chinese feels different. It's not just new words for yesterday or tomorrow. The truth is, it's a different way of thinking about time itself — more visual, more logical, and strangely freeing once you get it. Basically, you're placing your event on a timeline using a few key characters and a fixed word order. Allow me to explain in details of how this grammar works!

- The word order of expressing time in Chinese Mandarin

- Simple markers to tell time in Chinese: 上, 这, and 下

- Duration of time vs. Point-in-time: Two distinct Chinese time usages

- Navigating the vocabulary to tell general time of the past, present, and future

- Vague time periods and the time-related flow: 以前, 以后, and 然后

- Ask for the time in real-life situations: 什么时候, 几点, 多久

- Common pitfalls and how to sidestep them to talk about time correctly

- Practical tips for making Chinese time system stick

- FAQs

The word order of expressing time in Chinese Mandarin

To talk about time, we need to learn Chinese word order first. In Mandarin Chinese, you almost always establish when something happens before you say what happens or who does it.

The core formula is simple: Time + (Subject) + Action.

Think of it like setting the stage. You don't say "I will meet a friend tomorrow." You set the scene first:

-

。

Tomorrow I will meet a friend.

The time in Mandarin Chinese (Tomorrow) is the very first piece of information. This applies to clock times, days, and broader time periods.

-

。

Afternoon three o’clock we have a meeting. -

。

Last year I went to Shanghai.

This might feel backward at first. But the more you practice where to place the expressions of time in Chinese language, the more logical it becomes. You're providing the context upfront. In other words, you're telling your listener the temporal chapter before giving them the story. It's the most fundamental habit to build, and it makes your speech instantly more native-sounding.

Simple markers to tell time in Chinese: 上, 这, and 下

Once you accept the time-first rule, you need your main vocabulary pins. The beautiful part is how consistent and logical the system is.

For days, weeks, months, and years in Chinese time, you'll use a powerful trio: (Last), (This), and (Next).

Look at the pattern of these Chinese phrases.

- Yesterday is (Yesterday).

- Last week is (Last week).

- Last month is (Last month).

- Last year is (Last year).

- Tomorrow is (Tomorrow).

- Next week is (Next week).

- Next month is (Next month).

- Next year is (Next year).

- This week is (This week).

- This month is (This month).

- This year is (This year).

You'll love how this pattern repeats. It takes the guesswork out. If you know (Week), you automatically know , , and . More or less, you've just learned nine phrases with three words in Chinese time system.

Duration of time vs. Point-in-time: Two distinct Chinese time usages

This is a classic stumbling block, but conquering it is a game-changer. Chinese makes a crucial distinction between how long something lasted (Duration) and when it happened (A point-in-time). Mixing these up is a very common mistake.

Express time and duration in Mandarin Chinese

For stating a duration — the length of an action — you often use the particle placed after the verb and the time period. The structure focuses on the span. For example:

-

。

I studied Chinese for three years. (The emphasis is on the three-year journey.) -

。

He slept for ten hours.

Refer to a specific time in Mandarin

For indicating a point-in-time — a moment or period when something occurred — you use the Chinese word (At the time of). This sets the scene.

-

……

When I was studying Chinese... (This exact time introduces what happened during that era. The difference is critical.) -

……

When I lived in Beijing... (A backdrop for another story.)

Navigating the vocabulary to tell general time of the past, present, and future

Chinese verbs don't change form for tense. The truth is, time is indicated by context, time words, and a few powerful particles. This seems daunting but it's actually quite straightforward once you stop looking for conjugations.

Past tense time expressions

The particle is your primary signal for a completed action or change of state, often (but not always) placing an event in the past.

-

。

I yesterday bought a piece of clothing. (The tells you 'when', and the confirms the action is done.)

For life experiences, use :

-

。

I haven’t eaten this before.

Chinese vocabulary for future tense

The future is often clear from time words like (Tomorrow). You can add (Will) or (Going to) for clarity:

-

。

I next month am going to travel.

Core phrases for present ongoing time in Mandarin Chinese

For present ongoing action, use or :

-

。

She is reading a book.

So, in other words, you're adding clear signposts around a stable, unchanging verb. It's efficient and clean.

Vague time periods and the time-related flow: 以前, 以后, and 然后

Life isn't just isolated points; it's a sequence. To talk about before, after, and then, you have a brilliant set of tools. These words help you link events on your timeline.

- (Before) means 'before' or 'ago'. It can be used after a verb phrase: (Before eating). Or with a time period: (Three years ago).

- (After) means 'after' or 'later'. (After getting off work), (Five minutes later).

- (Then) is your go-to for 'then' or 'after that', showing the next step in a sequence. (I first go home, then cook). It’s the glue for storytelling.

Basically, with , , and , you can map out any series of events clearly and naturally, which is the whole point of talking about time. Sometimes you will notice that many Chinese learners, also Chinese native speakers, use a lot as a filler, unconsciously. To overcome this, you can try to record yourself on a speech, and then consciously replace with a natural pause.

Ask for the time in real-life situations: 什么时候, 几点, 多久

So, you've learned how to state when things happen. But what about when you need to ask? This is where you turn the structure around, and it’s just as logical. The thing is, asking about time is often easier than explaining it, because you're using a clear set of question words that slot right into the sentence patterns you already know.

Your most important tool is (When). It’s your direct substitute for a time phrase. Remember the golden rule? Time comes first. So does the question word for time. You simply replace the time slot in your sentence with .

-

?

When will you come? -

?

When will the gala begin?

For a more specific "what time," use (What time).

-

?

What time do we meet? -

?

What time is it now?

But here’s the nuance we discussed earlier: you must choose your question based on whether you want a point in time or a duration.

If you want to know how long something takes, you ask (How long) or (What length of time).

-

?

How long are you going to go?

If you want to know since when, you use (From when start).

-

?

Since when did you start learning Chinese?

Basically, you're just taking the declarative structures and swapping in the right interrogative word. If you're a person who likes clear systems, you'll love this consistency. The question word simply occupies the same grammatical territory as the answer would.

Common pitfalls and how to sidestep them to talk about time correctly

Let's preempt some frustration. Here are mistakes I made, so you don't have to.

- First, forcing English prepositions. You don't need a word for 'at' in (I three o’clock eat). Adding one is wrong. The time phrase stands alone.

- Second, overusing 了. It doesn't equal English past tense. It marks completion. If you're stating a past fact without emphasizing it's finished, you might not need it. (Yesterday I was at home) is often fine without 了. The downside to overusing it is sounding unnatural.

- Finally, the classic word order slip. When you're nervous, you might blurt out . It happens. The fix is slow, deliberate practice of the Time + Subject + Action formula until it's muscle memory. Write it out. Say it out loud. Your brain will rewire itself.

Practical tips for making Chinese time system stick

Learning this system can feel abstract, so here are concrete tips from my own journey. In short - you have to practice building the timeline visually.

- First, drill the core word order of Chinese grammar religiously. Write ten simple sentences daily using the Time + Subject + Action formula. Use 今天 (Today), (Evening eight o’clock), (Next week). This isn't creative work; it's construction training.

- Second, tackle the duration vs. point-in-time hurdle with a two-column list. On one side, write duration in Chinese sentences. On the other, write point-in-time sentences using . Force yourself to see and feel the difference. A classic mistake is mixing these up, so preempt that confusion.

- Finally, listen for time markers. When watching a show or listening to a podcast, just focus on catching the time words. (Then), (After), (Before). Notice where they are in the sentence.

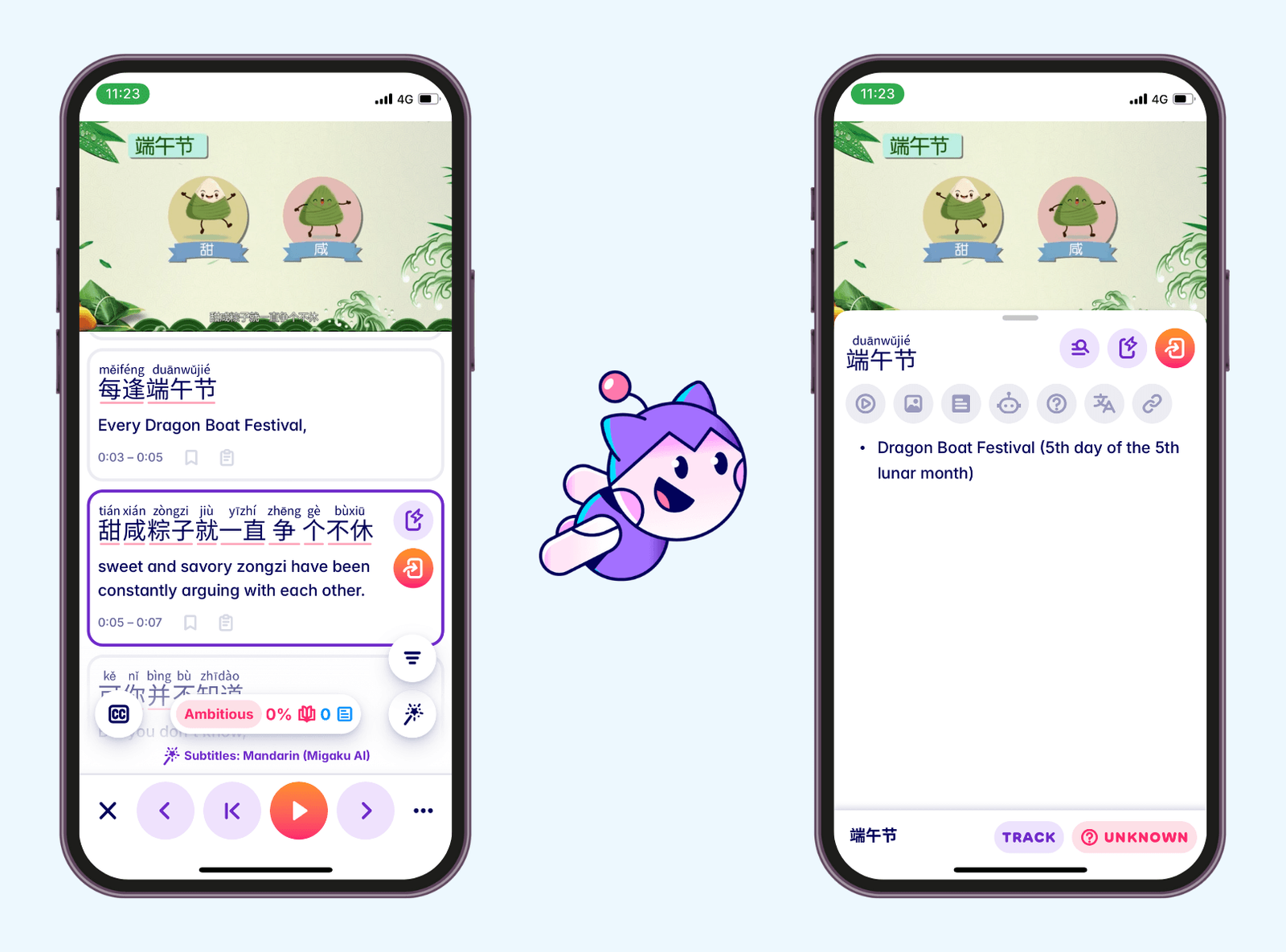

Anyway, if you want to practice these time expressions with real Chinese content, Migaku's browser extension and app let you look up words and phrases instantly while watching shows or reading articles. Makes learning from immersion way more practical. There's a 10-day free trial if you want to check it out.

FAQs

Pick up Chinese vocabulary for time from reality

The final step is passive immersion. Follow Chinese social media or vloggers. When you see a post titled (My last weekend), you’ve just reviewed the time-first rule. Hearing (We’ll see each other later) drills sequence. Your media feed becomes a continuous, living quiz.

If you consume media in Chinese, and you understand at least some of the messages and sentences within that media, you will make progress. Period.

Connect your study directly to the rhythm of daily life.