Japanese Negation: How to Make Negative Sentences in Japanese Grammar

Last updated: December 30, 2025

So you want to say "no" in Japanese? Well, get ready, because Japanese negation works completely differently from English. The good news is that once you understand the patterns, making negative sentences becomes pretty straightforward. The bad news? You've got multiple verb types to deal with, formal versus informal styles, and a bunch of conjugation rules to memorize. Let's break down exactly how Japanese negation works, starting with the basics and working our way up to the trickier stuff.

Understanding Japanese negation basics

Japanese uses different negative forms depending on what you're negating. Verbs, adjectives, and nouns all have their own rules. The most common pattern you'll see is adding nai (ない) for informal negation and masen (ません) for formal negation.

Unlike English where you just slap "not" into a sentence, Japanese requires you to conjugate the verb itself into a negative form.

Think of it like this: you're transforming the entire word, rather than adding a separate negation word.

The particle wa (は) often appears in negative sentences to mark the topic, just like in regular Japanese sentences. You'll see patterns like "watashi wa tabenai" () meaning "I don't eat" or "I won't eat."

Negative form for verbs

Verbs are where most learners spend their time with negation, and for good reason. You'll use negative verb forms constantly in everyday conversation.

Ru-verbs (Group 2 verbs)

Ru-verbs are the easiest to negate. You literally just drop the ru (る) and add nai (ない) for informal or masen (ません) for formal.

Let's look at taberu (), which means "to eat":

- Informal negative: tabenai () meaning "don't eat" or "won't eat"

- Formal negative: tabemasen () meaning "don't eat" or "won't eat" (Polite)

Another example with miru () meaning "to see" or "to watch":

- Informal: minai () meaning "don't see" or "won't see"

- Formal: mimasen () meaning "don't see" or "won't see" (Polite)

Pretty straightforward, right? The conjugation pattern stays consistent across all ru-verbs.

U-verbs (Group 1 verbs)

U-verbs require a bit more work. You need to change the final u (う) sound to the corresponding a sound, then add nai (ない) for informal or masen (ません) for formal.

Take kaku () meaning "to write":

- The ku (く) changes to ka (か)

- Add nai (ない) to get kakanai () meaning "don't write"

- Or add masen after the stem kaki to get the formal kakimasen ()

Wait, that formal one looks different! For formal negation with u-verbs, you actually use the masu (ます) stem. So kaku becomes kakimasu in formal positive, and kakimasen in formal negative.

Let's try nomu () meaning "to drink":

- Informal negative: nomanai () meaning "don't drink"

- Formal negative: nomimasen () meaning "don't drink" (Polite)

The mu (む) changed to ma (ま) for the informal, and we used the masu stem nomi for the formal version.

Here's a quick reference for the sound changes in u-verbs:

- ku → ka (like kaku → kakanai)

- gu → ga (like oyogu → oyoganai)

- su → sa (like hanasu → hanasanai)

- tsu → ta (like matsu → matanai)

- nu → na (like shinu → shinanai)

- bu → ba (like asobu → asobanai)

- mu → ma (like nomu → nomanai)

- ru → ra (like kaeru → kaeranai)

- u → wa (like kau → kawanai)

Irregular verbs

Japanese has two main irregular verbs that you absolutely need to memorize: suru (する) meaning "to do" and kuru () meaning "to come."

For suru:

- Informal negative: shinai (しない) meaning "don't do"

- Formal negative: shimasen (しません) meaning "don't do" (Polite)

For kuru:

- Informal negative: konai () meaning "don't come"

- Formal negative: kimasen () meaning "don't come" (Polite)

These don't follow the normal patterns, so you've just got to drill them until they stick.

Past tense negatives

Alright, so you've got present tense negation down. Now let's add past tense into the mix.

For informal past negative, you take the negative form ending in nai (ない) and conjugate nai as if it were an i-adjective. Change the i (い) to katta (かった).

Using taberu () again:

- Present negative: tabenai () meaning "don't eat"

- Past negative: tabenakatta () meaning "didn't eat"

With kaku ():

- Present negative: kakanai () meaning "don't write"

- Past negative: kakanakatta () meaning "didn't write"

For formal past negative, you take the masen (ません) form and change it to masen deshita (ませんでした).

Examples:

- tabemasen deshita () meaning "didn't eat" (Polite)

- kakimasen deshita () meaning "didn't write" (Polite)

This pattern holds across all verb types. Once you know the present negative, forming the past negative follows the same rules every time.

Negating adjectives

Japanese has two types of adjectives, and they negate differently.

I-adjectives

I-adjectives end in i (い) in their dictionary form.

To negate them, drop the final i and add kunai (くない) for informal or ku arimasen (くありません) for formal.

Take takai () meaning "expensive" or "tall":

- Informal negative: takakunai () meaning "isn't expensive"

- Formal negative: takaku arimasen () meaning "isn't expensive" (Polite)

Another example with oishii () meaning "delicious":

- Informal negative: oishikunai () meaning "isn't delicious"

- Formal negative: oishiku arimasen () meaning "isn't delicious" (Polite)

For past tense, use kunakatta (くなかった) for informal or ku arimasen deshita (くありませんでした) for formal.

Na-adjectives

Na-adjectives work more like nouns.

You add ja nai (じゃない) or dewa nai (ではない) for informal negation, and ja arimasen (じゃありません) or dewa arimasen (ではありません) for formal.

Using kirei (きれい) meaning "pretty" or "clean":

- Informal negative: kirei ja nai (きれいじゃない) meaning "isn't pretty"

- Formal negative: kirei ja arimasen (きれいじゃありません) meaning "isn't pretty" (Polite)

The dewa versions sound more formal and are more common in writing, while ja versions are more conversational.

Negating nouns

To negate a noun, you use ja nai (じゃない) or dewa nai (ではない) for informal, and ja arimasen (じゃありません) or dewa arimasen (ではありません) for formal.

This is basically the same as na-adjectives.

You might be wondering: is it dewanai or janai? Both are correct. Dewa nai (ではない) is more formal, while ja nai (じゃない) is conversational. You'll hear ja nai way more often in daily speech.

Examples with gakusei () meaning "student":

- Informal: gakusei ja nai () meaning "isn't a student"

- Formal: gakusei ja arimasen () meaning "isn't a student" (Polite)

The copula desu (です) becomes ja nai desu (じゃないです) in casual polite speech, though technically ja arimasen is more grammatically correct for formal situations.

Answering questions with negation

When someone asks you a yes/no question in Japanese, you answer with hai (はい) for yes or iie (いいえ) for no, then typically follow up with the appropriate verb form.

Question:

?

Do you speak Japanese?

Negative answer:

。

No, I don't speak.

You can also just use the negative verb alone without iie in casual conversation. The verb form makes it clear you're saying no.

Here's something that confuses English speakers: if someone asks a negative question like "Don't you like sushi?" and you want to say you DO like it, you still say hai (はい) in Japanese. The logic is different from English. You're confirming or denying the statement itself.

Question:

?

Don't you like sushi?

If you like sushi:

。

No (to your negative assumption), I like it.

If you don't like sushi:

。

Yes (you're correct), I don't like it.

This trips up a lot of learners, so pay attention to the pattern.

Partial negation and double negatives

Partial negation in Japanese uses words like amari (あまり) meaning "not very" or zenzen (全然) meaning "not at all." These words pair with negative verb forms to express degree.

-

。

Not very delicious. (The amari softens the negation.) -

。

Don't understand at all. (The zenzen emphasizes complete negation.)

Double negatives in Japanese work differently than in English. When you use a negative verb with a negative potential form, you're actually creating emphasis rather than canceling out the negation.

For example, literally translates to something like "it's not that I can't not go," which means "I have to go" or "I have no choice but to go." These constructions sound formal and are more common in written Japanese or formal speech.

Another pattern uses meaning "must do." Literally this is "if you don't do it, it won't work," but it functions as an obligation expression.

Common mistakes with Japanese negative sentences

One mistake beginners make is trying to use a separate word for "not" like in English. You can't just stick nai (ない) randomly into a sentence. You need to conjugate the verb properly.

Another common error is mixing up the verb groups. If you treat a u-verb like a ru-verb, you'll create nonsense words. Kaku () doesn't become kakunai. It becomes kakanai ().

Some learners also forget that aru (ある) meaning "to exist" (for inanimate objects) has an irregular negative: nai (ない). Not aranai or arinai, just nai.

Similarly, iru (いる) meaning "to exist" (for animate beings) becomes inai (いない), which follows the ru-verb pattern but looks a bit odd because the stem is so short.

Moving forward with negation in Japanese grammar

Honestly, the best way to get comfortable with Japanese negation is just to practice. A lot.

- Make flashcards with verb conjugations.

- Write out negative sentences. Try to negate everything you see during your study sessions.

- Pay attention to negative forms when you're consuming Japanese media. You'll hear nai (ない) and masen (ません) constantly in anime, dramas, and conversations. The more you expose yourself to these patterns, the more natural they'll become.

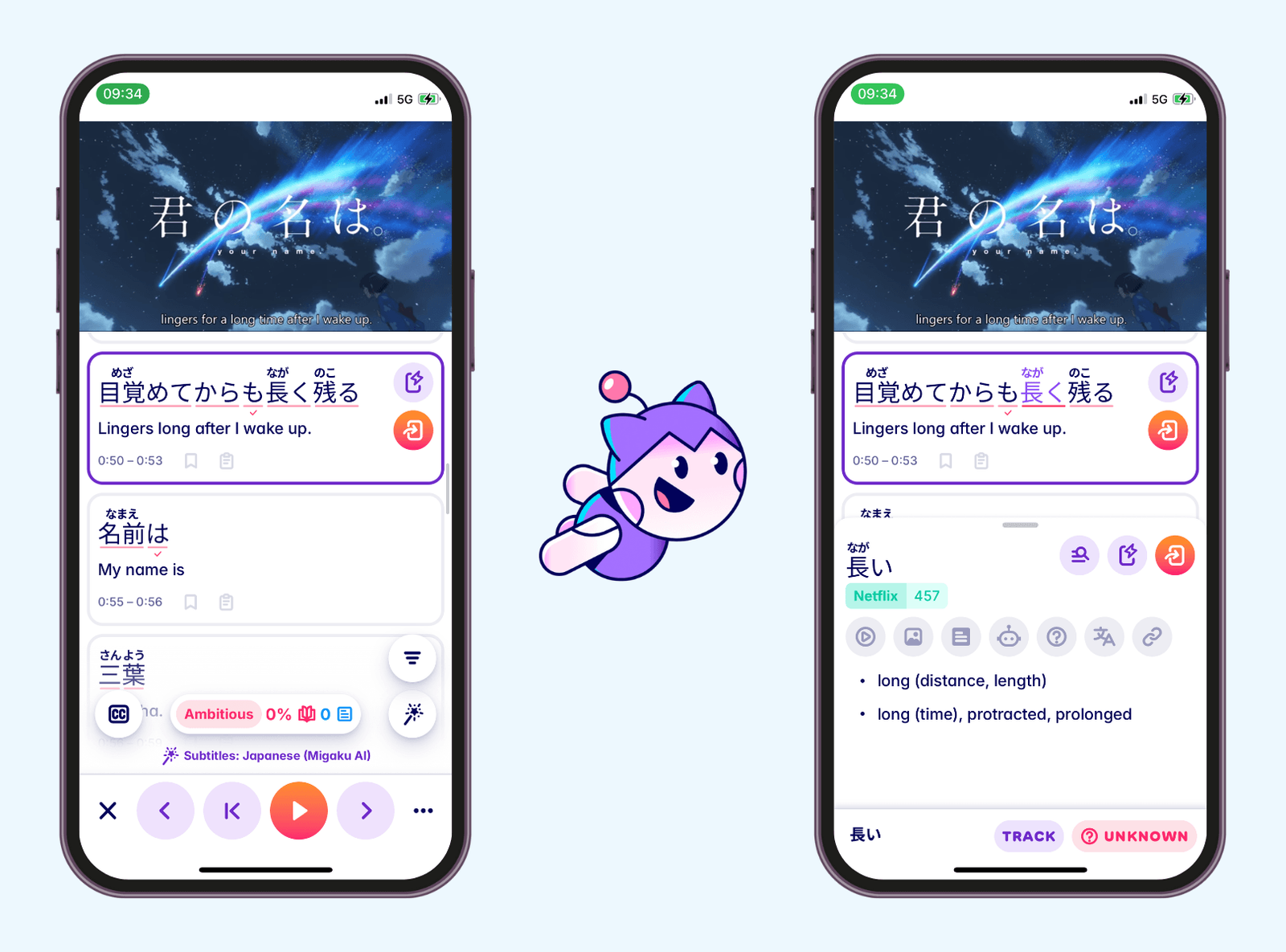

Anyway, if you want to practice spotting these negative forms in real Japanese content, Migaku's browser extension and app let you look up words and grammar patterns instantly while watching shows or reading articles. Makes it way easier to learn from actual native content instead of just textbook examples. There's a 10-day free trial if you want to check it out.

Making the first step is more important than perfection when learning conjugation rules

Don't stress too much about getting every conjugation perfect right away. Even if you mess up and say taberunai instead of tabenai, Japanese speakers will usually understand what you mean. The important thing is to keep practicing and gradually refine your accuracy as you consume more media extensively.

If you consume media in Japanese, and you understand at least some of the messages and sentences within that media, you will make progress. Period.

Try until you've made it!