Italian Emotions Vocabulary: Express Emotions in Italian Like a Native

Last updated: February 14, 2026

Learning Italian expressions of emotions goes way beyond just memorizing a list of adjectives. When you're actually talking to someone, you need to know which verbs work with which feelings, how to adjust words for gender, and what phrases Italians use in real conversations. This guide breaks down the essential Italian emotions vocabulary you need, from basic adjectives to idiomatic expressions that'll make you sound more natural.🙂

- Basic emotion adjectives to talk about feelings in Italian

- Expressing happiness and joy in Italian vocabulary

- Conveying love and affection using emotional expressions

- Describing fear, anger, and negative emotions in Italian

- Advanced and nuanced emotional vocabulary

- Idiomatic expressions that make you sound natural

- How verbs change everything when expressing feelings and emotions

- Gender agreement rules you need to know

- Common mistakes to watch out for

- Learning your vocabulary with practical methods

Basic emotion adjectives to talk about feelings in Italian

Let's start with the core emotional vocabulary that comes up constantly in Italian conversations. These adjectives form the foundation of expressing how you feel.

The most common positive emotion is felice (Happy). You'll hear this one everywhere. "Sono felice" means "I'm happy," and it works for both masculine and feminine speakers because felice doesn't change based on gender. Pretty convenient, right?

For sadness, you've got triste (Sad). Same deal here, no gender variations. "Mi sento triste" translates to "I feel sad."

When you're angry, the adjective arrabbiato comes into play. Here's where gender agreement matters. If you're a guy, you'd say "Sono arrabbiato." If you're a woman, it becomes "Sono arrabbiata." The ending changes from -o to -a.

Other essential adjectives include:

Italian (Masculine/Feminine) | English |

|---|---|

Stanco / stanca | Tired |

Nervoso / nervosa | Nervous |

Contento / contenta | Content, pleased |

Preoccupato / preoccupata | Worried |

Annoiato / annoiata | Bored |

Sorpreso / sorpresa | Surprised |

The gender variation pattern is consistent across most Italian adjectives. Masculine forms typically end in -o, feminine in -a. Plural forms change to -i for masculine and -e for feminine groups.

Expressing happiness and joy in Italian vocabulary

Beyond the basic felice, Italian offers several ways to express different shades of happiness and joy.

Contento/contenta works for general contentment or satisfaction. "Sono contento del risultato" means "I'm happy with the result." It's slightly less intense than felice, which carries more genuine joy or deep happiness.

For excitement, you'd use entusiasta or emozionato/emozionata. "Sono entusiasta di vederti!" translates to "I'm excited to see you!" The adjective entusiasta doesn't change for gender, which makes it easier to remember.

Some useful phrases for expressing happiness:

- Che bello!

How nice! / How wonderful! - Sono al settimo cielo

I'm on cloud nine (Literally "seventh heaven") - Mi fa piacere

It makes me happy / I'm pleased - Sono felicissimo / felicissima

I'm extremely happy

That last one uses the superlative form, adding -issimo/-issima to intensify the adjective. You can do this with most Italian adjectives to amp up the emotion.

Conveying love and affection using emotional expressions

Italian has a reputation for being the language of love, and yeah, there's plenty of vocabulary for expressing affection and romantic feelings.

The verb amare means "to love" in the deepest sense. "Ti amo" is reserved for serious romantic love or family. Don't throw it around casually unless you mean it.

For liking something or someone, voler bene works better in most situations. "Ti voglio bene" expresses affection and care without the intensity of "ti amo." You'd use this with friends, family members, or romantic partners in everyday contexts.

Other expressions of affection include:

- Sono innamorato / innamorata

I'm in love - Mi manchi

I miss you - Tenere a qualcuno

To care about someone - Affezionato / affezionata

Fond of, attached to

When describing someone you love, you might say "Mi fa battere il cuore" (You make my heart beat) or use the adjective caro/cara (Dear).

The phrase "mi piaci" means "I like you" in a romantic sense, while "mi piace" followed by a thing means you like that object or activity. The grammar shifts based on what you're talking about.

Describing fear, anger, and negative emotions in Italian

Let's get into the darker emotional vocabulary because, you know, life isn't all sunshine.🌧️

For fear, the main phrase uses avere: "Ho paura" (I'm afraid). You can specify what scares you with "di": "Ho paura dei ragni" (I'm afraid of spiders).

The adjective spaventato/spaventata means frightened or scared. "Sono spaventato" works when something has actively scared you.

Anxiety gets expressed through ansioso/ansiosa (Anxious) or preoccupato/preoccupata (Worried). The difference is subtle, ansioso leans more toward general anxiety while preoccupato suggests worry about something specific.

Anger and frustration have several options:

Italian (Masculine/Feminine) | English |

|---|---|

Arrabbiato / arrabbiata | Angry |

Furioso / furiosa | Furious |

Irritato / irritata | Irritated |

Stufo / stufa | Fed up, sick of something |

That last one is super useful. "Sono stufo di aspettare" means "I'm fed up with waiting."

For sadness beyond the basic triste, you've got:

Italian (Masculine/Feminine) | English |

|---|---|

Depresso / depressa | Depressed |

Deluso / delusa | Disappointed |

Scoraggiato / scoraggiata | Discouraged |

Abbattuto / abbattuta | Downcast, dejected |

The phrase "Mi sento giù" translates to "I feel down" and works for mild sadness or low mood.

Advanced and nuanced emotional vocabulary

Once you've got the basics down, you can expand into more specific emotional states that capture subtle feelings.

Nostalgia exists in Italian as nostalgia, but they also use "avere nostalgia di" to express missing something from the past. "Ho nostalgia dei vecchi tempi" means "I'm nostalgic for the old days."

For embarrassment, you've got imbarazzato/imbarazzata (Embarrassed) or vergognarsi (To feel ashamed). "Mi vergogno" means "I'm ashamed."

Frustration can be espressa through frustrato/frustrata, but Italians also say "Che frustrazione!" as an exclamation.

Some nuanced emotions:

Italian (Masculine/Feminine) | English |

|---|---|

Geloso / gelosa | Jealous |

Invidioso / invidiosa | Envious |

Orgoglioso / orgogliosa | Proud |

Commosso / commossa | Moved, touched emotionally |

Sollevato / sollevata | Relieved |

Confuso / confusa | Confused |

Sopraffatto / sopraffatta | Overwhelmed |

The adjective commosso is particularly useful because English doesn't have a perfect equivalent. It describes that feeling when something touches you emotionally, maybe bringing you close to tears from sentiment.

Idiomatic expressions that make you sound natural

Italian emotions vocabulary really comes alive when you learn the idiomatic phrases that native speakers actually use. These don't always translate literally, but they're gold for sounding more fluent.

- "Avere il morale a terra" literally means "to have morale on the ground," but it's used to say you're feeling really down or demoralized.

- "Essere su di giri" translates roughly to "being wound up" or feeling hyper and energized. The literal meaning relates to engine RPMs, which is kind of funny.

- "Perdere le staffe" means to lose your temper. The literal translation is "to lose the stirrups," like falling off a horse.

More useful idiomatic expressions:

Italian Idiom | English |

|---|---|

Avere le farfalle nello stomaco | To have butterflies in your stomach |

Essere al verde | To be broke, but literally "to be at the green" |

Non vedere l'ora | Can't wait, literally "not see the hour" |

Essere giù di morale | To be down in spirits |

Avere la testa tra le nuvole | To have your head in the clouds |

These phrases show up constantly in casual conversation. Learning them alongside basic adjectives gives you way more expressive range.

How verbs change everything when expressing feelings and emotions

Here's something that trips up a lot of learners: Italian uses different verbs for different types of emotions, and it doesn't always match English logic.

The verb sentirsi (To feel) works for most emotional states. You conjugate it reflexively: "Mi sento felice" (I feel happy), "Ti senti stanco?" (Do you feel tired?). This construction works smoothly for adjectives describing temporary emotional states.

But then you've got avere (To have), which Italians use for certain feelings where English speakers would say "to be." This creates some weird-looking phrases if you translate them literally.

Common expressions with avere:

Italian | English |

|---|---|

Avere paura | To be afraid (Literally "to have fear") |

Avere fame | To be hungry (Literally "to have hunger") |

Avere sete | To be thirsty |

Avere sonno | To be sleepy |

Avere freddo | To be cold |

Avere caldo | To be hot |

So when you want to say "I'm scared," you actually say "Ho paura" (I have fear). It feels strange at first, but you get used to it.

The verb essere (To be) also shows up with emotional adjectives, especially for more permanent or defining characteristics. "Sono una persona ansiosa" (I'm an anxious person) uses essere because you're describing a trait, not a temporary feeling.

Gender agreement rules you need to know

This comes up so much with emotional vocabulary that it deserves its own section. Italian adjectives must agree with the gender and number of what they're describing.

Basic pattern for regular adjectives:

- Masculine singular: -o (contento)

- Feminine singular: -a (contenta)

- Masculine plural: -i (contenti)

- Feminine plural: -e (contente)

Some adjectives end in -e for both genders in singular form, like felice or triste. These change to -i in plural for both genders.

When you're describing yourself, you use the adjective form that matches your own gender. "Sono stanca" if you're a woman, "Sono stanco" if you're a man.

If you're describing a group of people, masculine plural (-i) is used for all-male groups or mixed groups. Feminine plural (-e) only applies to all-female groups.

This might seem tedious, but getting gender agreement right makes a huge difference in how natural you sound. Native speakers notice when you mess it up.

Common mistakes to watch out for

Learning Italian emotions vocabulary comes with some predictable stumbling blocks.

- The biggest one is mixing up essere and avere constructions. English speakers want to say "Sono paura" (I am fear) instead of "Ho paura" (I have fear). You just have to memorize which emotions use which verb.

- Another common mistake is forgetting gender agreement. Saying "Sono felico" or "Sono felica" instead of the correct felice (which doesn't change). Or using masculine forms when you should use feminine, like a woman saying "Sono stanco" instead of "Sono stanca."

- People also struggle with reflexive verbs like sentirsi. You need the reflexive pronoun: "Mi sento triste," not just "Sento triste."

- Overusing "molto" (Very) is another telltale beginner move. While "Sono molto felice" works fine, learning superlative forms like felicissimo or using intensifiers like "davvero" (Really) sounds more natural.

- Don't directly translate English idioms. "I'm feeling blue" doesn't work in Italian. You'd say "Mi sento giù" or "Sono triste" instead.

Learning your vocabulary with practical methods

Okay, so you've got all these words and phrases. How do you actually learn them?

Flashcards work really well for emotions vocabulary because you can pair the Italian word with situations or facial expressions. Tools like Anki or Quizlet let you create custom decks with Italian on one side and English translations on the other.

But honestly, context beats raw memorization every time. Try keeping an emotion journal in Italian where you write a sentence or two each day about how you're feeling. "Oggi mi sento stanco perché ho lavorato troppo" (Today I feel tired because I worked too much). This reinforces both the vocabulary and the grammar patterns.

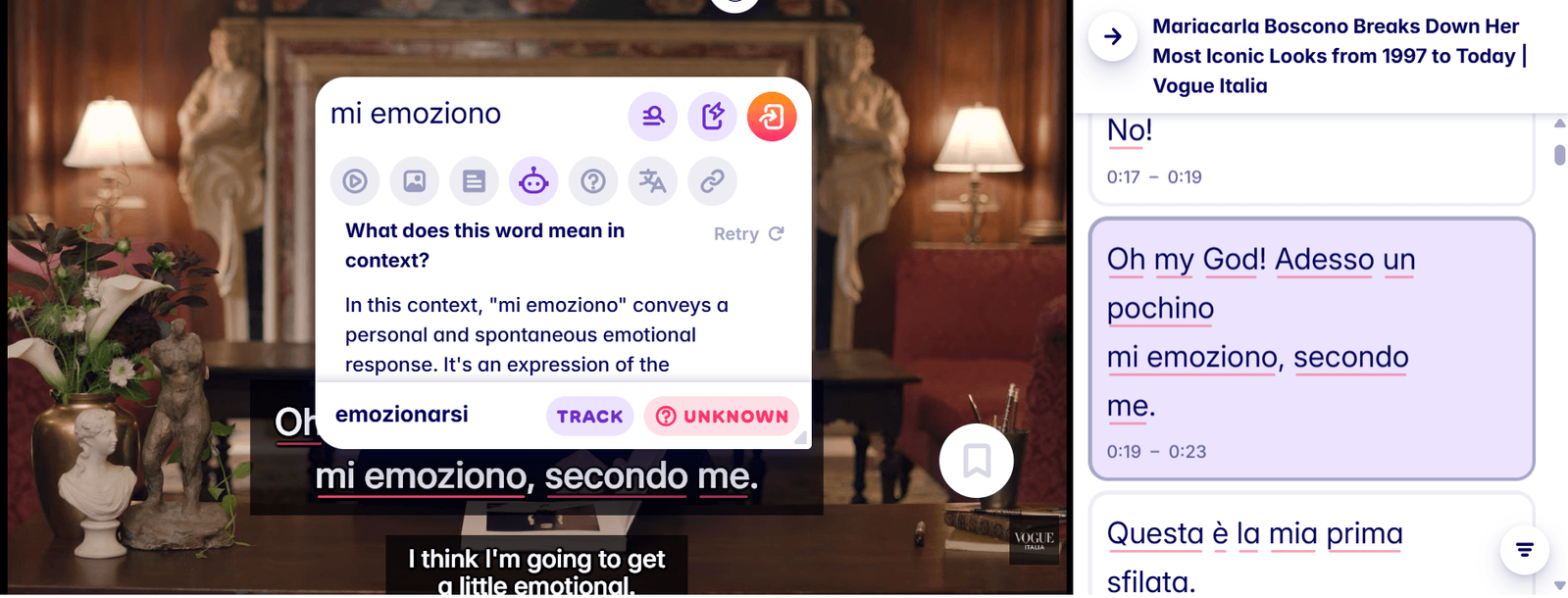

Watching Italian content helps massively because you see how people actually use these expressions. Pay attention to emotional scenes in shows or movies. When someone gets angry or sad, what words do they use? How do they construct the sentences?

Reading can also expose you to emotional vocabulary in context, especially if you're reading personal blogs, social media posts, or fiction where characters express feelings.

Anyway, if you're serious about learning Italian through real content instead of just vocabulary lists, Migaku's browser extension and app let you look up words instantly while watching Italian shows or reading articles. You can save words directly into flashcard decks and actually see how emotional vocabulary gets used in context. There's a 10-day free trial if you want to check it out.

Vocabulary lists are for beginners, not advanced learners

The key is moving beyond just memorizing lists. You need to practice using these words in sentences, understanding which verbs pair with which emotions, and getting comfortable with gender agreement. For advanced learners, context is everything.

If you consume media in Italian, and you understand at least some of the messages and sentences within that media, you will make progress. Period.

The more you learn, the easier it gets.