Japanese Calligraphy Guide: Learn the Art of Shodo, Japanese Traditional Art

Last updated: January 25, 2026

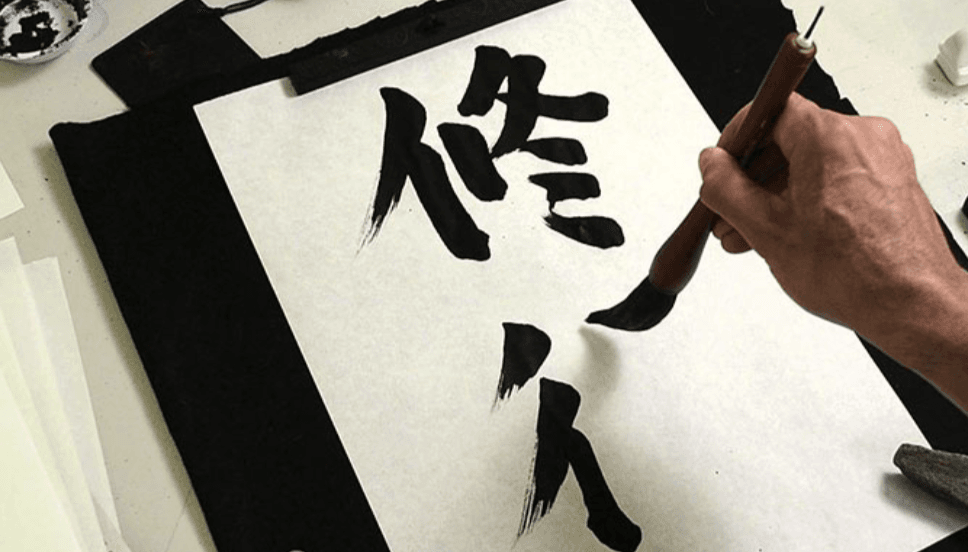

You've probably seen those gorgeous Japanese ink paintings with flowing characters. That's shodo (), the traditional art of Japanese calligraphy, and honestly, it's one of the most accessible ways to connect with Japanese culture. Whether you're learning Japanese or just curious about traditional arts, shodo offers this unique combination of artistic expression and meditative practice that's pretty addictive once you get started.

- What is Japanese calligraphy called

- A brief history of Japanese calligraphy

- Essential tools for shodo calligraphic practice

- Basic posture and brush holding techniques of a calligrapher

- Understanding the three main calligraphy writing styles

- Learning shodo fundamental strokes

- How shodo serves as a meditative practice in Japanese art

- Shodo in modern Japan and beyond

- Getting started with your shodo practice

- FAQs

What is Japanese calligraphy called

The art of Japanese calligraphy is called shodo or shodō (), which literally translates to "the way of writing."

The character 書 (sho) means "to write" and 道 (do/dō) means "path" or "way," the same character you'll find in judo () or kendo ().

This naming reflects something important: shodo goes beyond just beautiful handwriting. It's considered a spiritual and artistic practice with its own philosophy and techniques.

You might also hear it called shūji (), which means "learning characters," though this term usually refers to the practice of learning proper handwriting rather than the artistic discipline itself. When people talk about the traditional art form with its meditative and aesthetic dimensions, they use shodo.

A brief history of Japanese calligraphy

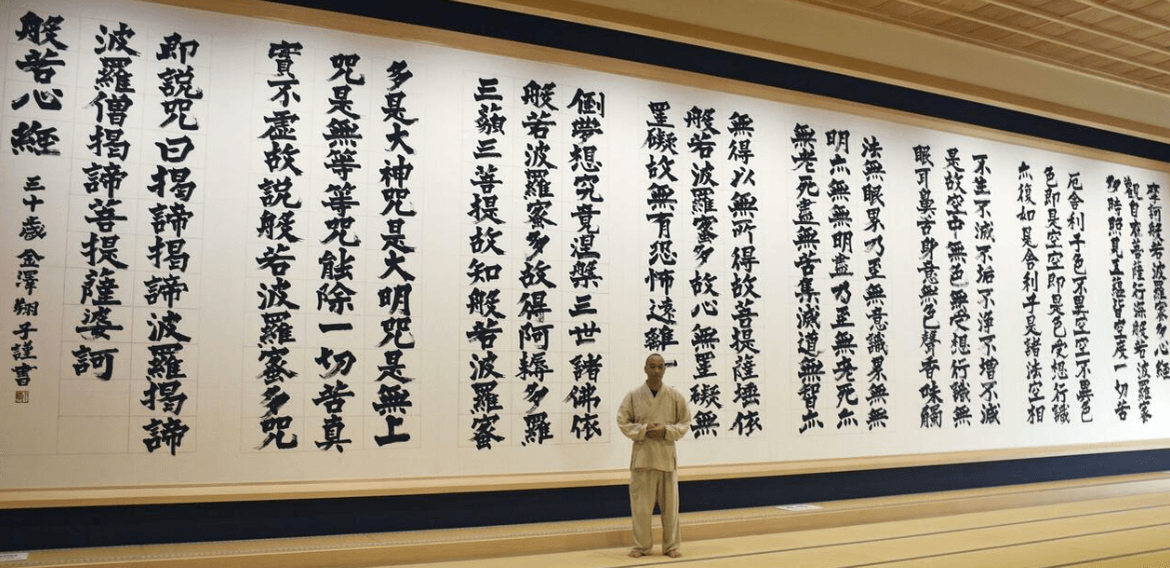

Japanese calligraphy traces its roots back to China, where brush and ink calligraphy developed thousands of years ago. Around the 6th century, Chinese characters and Buddhist texts made their way to Japan, bringing calligraphic traditions along with them. Buddhist monks played a huge role in spreading calligraphy throughout Japan, copying sutras by hand as both a religious practice and a way to preserve teachings.

Here's where things get interesting: while Japan initially copied Chinese styles, Japanese calligraphers eventually developed their own aesthetic.

By the Heian period (794-1185), Japan had created kana (かな), a phonetic writing system derived from simplified kanji. This allowed for a distinctly Japanese calligraphic style that was more flowing and cursive than traditional Chinese forms.

The connection between Buddhism and calligraphy remained strong throughout Japanese history. Zen Buddhism especially influenced shodo, emphasizing the meditative aspects of the practice. In Zen temples in places like Kyoto, monks would practice calligraphy as a form of moving meditation, believing that the state of mind directly influenced the quality of each stroke.

During the Edo period (1603-1868), calligraphy became more accessible to common people, moving beyond just monks and aristocrats. Schools started teaching it as part of basic education, and it became a valued skill across social classes.

This is the world's largest sutra calligraphy in Ryouunji.

Essential tools for shodo calligraphic practice

Traditional Japanese calligraphy uses a specific set of tools collectively known as bunbō-shihō (), meaning "four treasures of the study." These are the same basic tools that have been used for centuries.

- Fude () is your brush, and it's probably the most important tool you'll use. Traditional brushes have bamboo handles with bristles made from animal hair, goat, horse, or weasel hair being the most common. The bristles taper to a fine point, allowing you to create both thick and thin lines depending on pressure and angle. Brushes come in different sizes, but beginners usually start with a medium-sized brush around 8-10mm in diameter.

- Sumi () is the ink used in Japanese calligraphy. Traditional sumi comes as a solid ink stick that you grind against an ink stone with water to create liquid ink. The grinding process itself is considered part of the meditative preparation. These days, you can also buy bottled liquid sumi ink, which is way more convenient for beginners and produces similar results.

- Suzuri () is the ink stone where you grind your ink stick. It's usually made from slate or ceramic and has a flat grinding surface with a small well to collect the liquid ink. If you're using bottled ink, you still need a small dish to pour it into for dipping your brush.

- Washi () is traditional Japanese paper. Real washi is handmade from plant fibers and has this beautiful texture that absorbs ink in a specific way. The paper is usually thin and slightly absorbent, which means you can't really erase or fix mistakes. Each stroke is permanent, which adds to the mindfulness required.

You'll also want an underlay or shitajiki (), which is a soft mat you place under your paper. This provides cushioning and helps the brush move smoothly. A paperweight or bunchin () keeps your paper from sliding around while you work.

Basic posture and brush holding techniques of a calligrapher

Before you make your first stroke, you need to set up properly.

Traditional shodo is done sitting in seiza (), the formal Japanese kneeling position, at a low table. But honestly, you can also practice sitting in a chair at a regular table if seiza is uncomfortable. The key is keeping your back straight and your shoulders relaxed.

Hold the brush vertically, perpendicular to the paper. Grip it between your thumb and first two fingers, about one-third of the way up the handle. Your grip should be firm enough to control the brush but relaxed enough to allow fluid movement. This is different from holding a pen, where you typically angle it and rest it against your hand.

Your non-writing hand should rest on the table or gently hold the paper steady. Keep your wrist slightly elevated off the table, your whole arm should move as one unit when making strokes, not just your fingers or wrist.

The brush should move from your shoulder and core, creating smooth, controlled movements. This takes practice because it feels completely different from regular writing.

Understanding the three main calligraphy writing styles

Japanese calligraphy has three primary styles that range from formal and structured to flowing and expressive.

- Kaisho () is the standard block script, the most formal and easiest to read. Each stroke is clear and distinct, characters are balanced and proportional. Think of it as the equivalent of printed text. This is where beginners start because it teaches you the fundamental strokes and proper character structure. When you see signs or formal documents in Japanese, they're usually in kaisho.

- Gyōsho () is the semi-cursive script, a middle ground between formal and flowing. Some strokes connect, and the characters have more movement and rhythm than kaisho. It's faster to write than block script but still readable. This style is commonly used in everyday handwriting by Japanese people.

- Sōsho () is the cursive or "grass" script, highly stylized and flowing. Characters are heavily abbreviated and strokes flow together, making it beautiful but difficult to read if you don't know the specific forms. Master calligraphers often use sosho for artistic pieces because it allows the most personal expression and dynamic energy.

Each style requires different techniques and conveys different feelings. Kaisho shows discipline and clarity, gyosho suggests natural flow, and sosho expresses freedom and spontaneity.

Learning shodo fundamental strokes

All kanji and kana are built from a set of basic strokes. Mastering these is essential before attempting full characters.

- The horizontal stroke or yoko-sen () moves from left to right. You start with the brush tip, press down slightly to create width, then lift gradually as you finish. The stroke should have a slight taper at both ends.

- The vertical stroke or tate-sen () moves top to bottom. Press firmly at the beginning, maintain even pressure through the middle, and finish with a decisive stop or slight hook depending on the character.

- The left-falling stroke or hidari-harai () sweeps diagonally down and to the left, gradually lifting the brush to create a tapered end. This stroke requires smooth acceleration and a confident finish.

- The right-falling stroke or migi-harai () is similar but moves down and to the right. This stroke often appears at the end of characters and should have an elegant, sweeping quality.

- Dots or ten () might seem simple, but they require precise control. The brush touches down, presses briefly, and lifts cleanly.

- Hooks and turns combine multiple directional changes within a single stroke. These take practice to make smooth and natural-looking.

The order and direction of strokes matter. Japanese follows specific stroke order rules that affect the character's balance and flow. Generally, you write top to bottom, left to right, with horizontal strokes before vertical ones.

How shodo serves as a meditative practice in Japanese art

There's something genuinely calming about shodo that goes beyond just creating art. The preparation alone sets a meditative tone. Grinding your ink stick against the stone, the repetitive circular motion and the gradual darkening of the water, creates a natural transition into a focused state of mind.

- When you're actually writing, you have to be completely present. There's no room for distraction because each stroke happens in a single moment. You can't pause halfway through a stroke or go back to fix it. This demands total concentration and acceptance of whatever emerges.

- The connection between mind and brush is immediate. Your mental state shows up directly in your strokes. Tension creates stiff, hesitant lines. Calmness produces smooth, confident movements. Over time, you become more aware of your internal state through observing your work.

Buddhist and Zen philosophy deeply influenced how shodo developed as a meditative practice. The idea of mushin (), meaning "no-mind" or empty mind, applies perfectly to calligraphy. You're aiming for that state where thinking stops and movement becomes natural and spontaneous.

Many practitioners describe entering a flow state during calligraphy sessions, where time seems to disappear and self-consciousness fades. It's similar to meditation but with the added element of creative expression.

Shodo in modern Japan and beyond

Calligraphy remains an important part of Japanese culture today. Kids learn basic shodo in elementary school as part of their education. Many people continue practicing throughout their lives, and calligraphy classes for adults are popular across Japan.

The New Year tradition of kakizome (), the first calligraphy writing of the year, is still widely practiced. People write aspirational words or phrases that represent their hopes for the coming year.

Contemporary calligraphers are also pushing boundaries, creating installations, performances, and fusion works that combine traditional techniques with modern aesthetics. You'll see calligraphic elements in graphic design, fashion, and advertising throughout Japan and increasingly worldwide.

For visitors to Japan, many temples and cultural centers in cities like Kyoto offer calligraphy workshops where you can try your hand at shodo and take home your creation. These experiences give you a hands-on appreciation for the art form.

The international interest in shodo has grown significantly, with practitioners and teachers around the world. You can find calligraphy societies and classes in most major cities, making it accessible even if you're not in Japan.

Getting started with your shodo practice

If you want to try shodo yourself, start simple. You can find beginner calligraphy sets online or at art stores that include a brush, ink, and practice paper. These starter kits usually cost between $20-50 and have everything you need to begin.

Start with basic strokes before attempting full characters. Spend time just making horizontal and vertical lines, getting comfortable with brush control and pressure. This might feel boring, but it builds the foundation for everything else.

Practice the character ichi (), which means "one" and is literally a single horizontal stroke. Despite being simple, making a beautiful horizontal stroke that's balanced and confident takes real skill.

Move on to simple characters like ni () meaning "two," san () meaning "three," or ki () meaning "tree." These teach you how strokes combine to form balanced compositions.

Consider following online tutorials or taking a class if you have access to one. Watching an experienced calligrapher demonstrate techniques helps way more than just reading descriptions. There are some solid YouTube channels and online courses specifically for shodo beginners.

Set up a regular practice routine, even if it's just 15-20 minutes a few times a week. Consistency matters more than marathon sessions. The physical skills and mental focus both develop gradually through repeated practice.

Don't worry about creating masterpieces right away. Focus on the process, the feeling of the brush moving across paper, the rhythm of your breathing, the moment-to-moment experience. The artistic results will improve naturally as you practice.

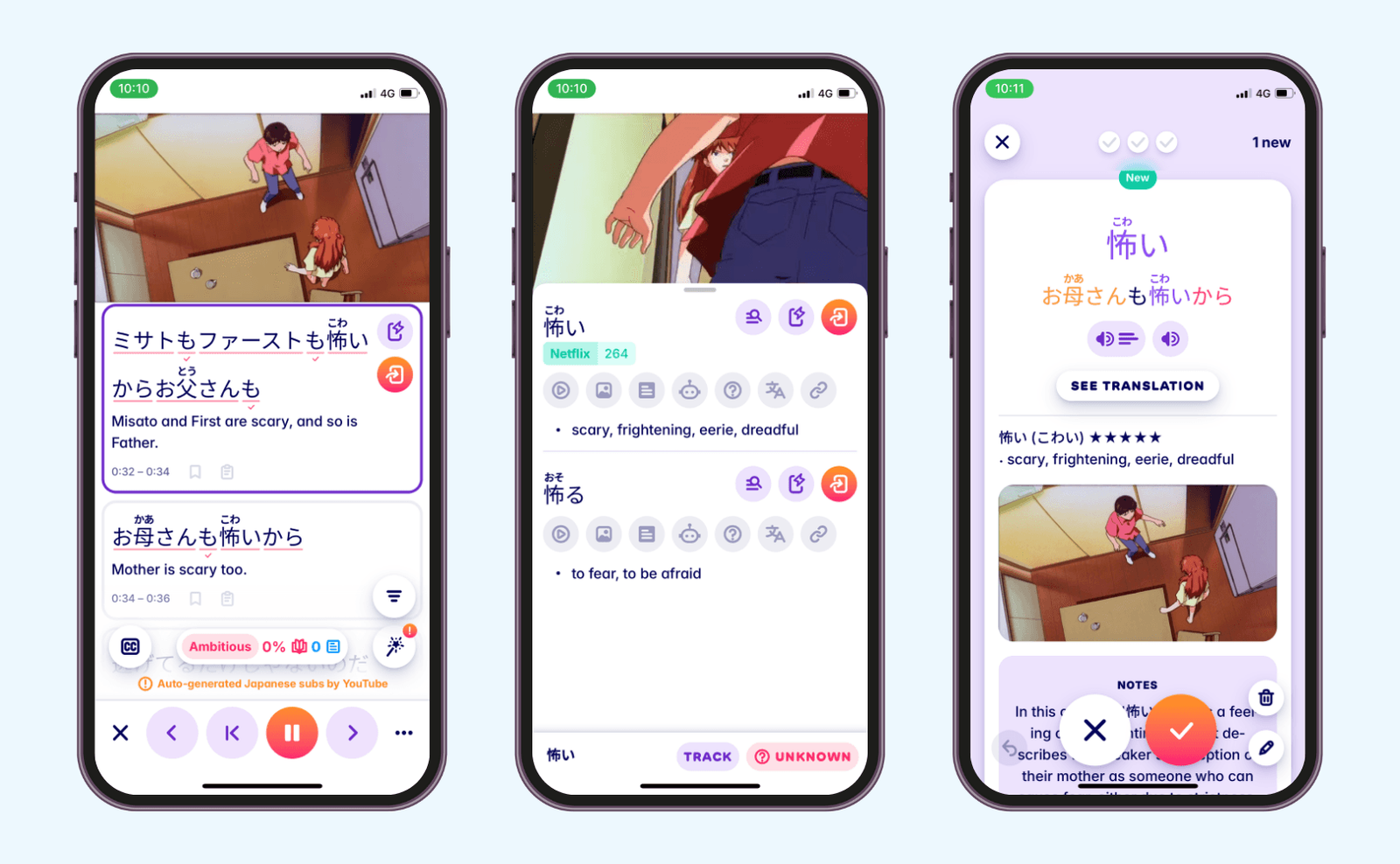

Anyway, if you're interested in Japanese language and culture, Migaku's browser extension and app can help you learn while consuming content you actually enjoy. You can look up words instantly while reading articles about calligraphy or watching videos of master calligraphers at work. There's a 10-day free trial if you want to check it out.

FAQs

Dig into the meanings behind the black ink

You might want to know the meanings of the calligraphy pieces you've been copying or writing, be it a poem, a quote, or some other content. The combination of Japanese language learning and calligraphy practice is particularly powerful. As you learn new vocabulary and kanji, practicing them through shodo reinforces the learning while creating something beautiful. When you practice a new shodo piece, you are also learning the words and expressions.

If you consume media in Japanese, and you understand at least some of the messages and sentences within that media, you will make progress. Period.

There is more than one way to approach a foreign culture!