Japanese Causative Form: Guide on Causative and Causative-Passive Forms With Particles

Last updated: January 18, 2026

Ever get confused by Japanese causative form when learning Japanese? You're definitely not alone. The causative form trips up pretty much everyone. You're dealing with させる (saseru) endings, particles that seem to change randomly, and the whole "make versus let" distinction that doesn't always translate cleanly from English. I'm going to break down exactly how the causative form works, how to conjugate it properly, and when to use which particles. We'll cover the causative-passive too, because that combination confuses everyone at first.

What the Japanese causative form does

The causative form lets you express making someone do something or letting someone do something.

In Japanese, both of these meanings use the same grammatical structure, which feels weird at first if you're coming from English.

When you see a verb like (tabesaseru), it means "to make/let someone eat." The context tells you whether it's forced or permitted. If a parent says (kodomo ni yasai wo tabesaseru), they're probably making their kid eat vegetables. If someone says (tomodachi ni keeki wo tabesaseru), they're likely letting their friend eat cake.

The causative form transforms any verb into a transitive verb that requires a subject (The person causing the action) and an object (The person performing the action). This is why particles matter so much with causatives.

How to conjugate the causative form

Let me walk you through conjugating verbs into the causative form. The process differs depending on whether you're working with a godan verb, ichidan verb, or irregular verb.

Godan verbs (う-verbs)

For godan verbs, you change the final う (u) sound to the あ (a) sound in the same consonant row, then add せる (seru).

Here are more examples:

- (hanasu) "to speak" becomes (hanasaseru)

- (matsu) "to wait" becomes (mataseru)

- (nomu) "to drink" becomes (nomaseru)

- (asobu) "to play" becomes (asobaseru)

- (oyogu) "to swim" becomes (oyogaseru)

Ichidan verbs (る-verbs)

Ichidan verbs follow a simpler pattern. You drop the る (ru) and add させる (saseru).

Examples:

- (taberu) "to eat" becomes (tabesaseru)

- (oshieru) "to teach" becomes (oshiesaseru)

- (okiru) "to wake up" becomes (okisaseru)

Irregular verbs

Japanese has two main irregular verbs: する (suru) "to do" and (kuru) "to come."

- する (suru) becomes させる (saseru). So (benkyou suru) "to study" becomes (benkyou saseru) "to make/let someone study."

- (kuru) becomes (kosaseru) "to make/let someone come."

The conjugation patterns stay consistent across all verb types, which is pretty cool once you get the hang of it.

Particles: に versus を

This is where things get interesting. The particle you use with causative verbs depends on whether the original verb is transitive or intransitive.

Intransitive verbs + に

When the original verb is intransitive (Doesn't take a direct object), you use に (ni) to mark the person you're making or letting do something.

The verb (iku) is intransitive. You say:

。

The teacher made the student go to the library.

The student is marked with に (ni) because (iku) doesn't normally take a direct object.

Transitive verbs + を

When the original verb is transitive (Takes a direct object), you typically use を (wo) to mark the person doing the action.

The verb (taberu) is transitive. You say:

。

The mother made the child eat vegetables.

Wait, that has two を (wo) particles, which feels awkward. In practice, Japanese speakers often switch the person marker to に (ni) to avoid the double を (wo):

。

Both versions are grammatically acceptable, but the に (ni) version sounds more natural.

The real pattern: に is used more often

Here's what actually happens in daily Japanese: に (ni) gets used way more often than を (wo) with causative verbs, regardless of whether the original verb is transitive or intransitive. The に (ni) particle just sounds better and avoids confusion.

You'll hear both, but に (ni) dominates in conversation. If you stick with に (ni) for the person and を (wo) for the object (If there is one), you'll sound natural most of the time.

Causative-passive form: The double whammy

The causative-passive form combines the causative with the passive form. This expresses being made to do something or being forced to do something. It's the ultimate "I didn't want to do this" grammatical structure.

To form the causative-passive, you first make the verb causative, then conjugate that causative verb into passive form.

For godan verbs, there's a shortcut. Instead of the full させられる (saserareru), you can use される (sareru).

The verb (kaku) "to write" becomes:

- Full form: (kakaserareru)

- Shortened form: (kakasareru)

Both mean "to be made to write." The shortened version sounds less clunky and gets used more in conversation.

For ichidan verbs, you use the full させられる (saserareru) pattern:

- (taberu) becomes (tabesaserareru) "to be made to eat."

Example sentence:

-

。

I was made to write kanji by the teacher.

The causative-passive form always implies some level of unwillingness or inconvenience. You wouldn't use it for something you wanted to do anyway.

For the causative-passive abbreviation for る-verbs, does the さ count as both the あ sound from the ない form and also as the replacement of せら? Kind of. The さ (sa) in される (sareru) represents the causative marker that merged with the passive ending. You're essentially compressing させられる (saserareru) by dropping the せら (sera) part and keeping just される (sareru). The あ (a) row sound is already there from the causative conjugation, so される (sareru) attaches directly to it.

Politeness levels with causative verbs

Causative verbs conjugate for politeness just like regular verbs. You add ます (masu) to make them polite.

- (ikaseru) becomes (ikasemasu) in polite form.

- (tabesaseru) becomes (tabesasemasu).

The causative-passive also takes ます (masu):

- (kakasareru) becomes (kakasaremasu).

Make or let someone: Reading context

Is this person making someone do something or letting them? You have to read the context. Japanese doesn't distinguish between "make" and "let" grammatically within the causative form itself.

This sentence, (kodomo wo asobaseru) could mean "make the child play" or "let the child play." If the parent is saying it while the kid wants to study, it's probably "make." If the kid has been begging to go outside, it's "let."

The surrounding context, tone, and situation tell you which meaning applies.

Sometimes the verb itself gives hints. (nakaseru) "to make someone cry" is almost always involuntary or negative. You're not "letting" someone cry in a permissive sense.

Common mistakes to watch out for

When you're learning causative conjugation, watch out for these common errors:

- Mixing up the particle choice. Remember that に (ni) works for basically everything and sounds natural. If you default to に (ni), you'll be right most of the time.

- Forgetting that causative verbs are themselves ichidan verbs. Once you've created (tabesaseru), it conjugates like a regular ichidan verb: (tabesasenai), (tabesaseta), (tabesasete).

- Using causative when you mean passive. (taberareru) and (tabesaseru) mean completely different things. The first is passive "to be eaten," the second is causative "to make/let someone eat."

- Overusing the causative-passive. Japanese learners sometimes go crazy with させられる (saserareru) forms. Native speakers use them, but usually only when the "being forced" nuance really matters. Don't throw causative-passive everywhere.

Practicing causative forms

- The best way to internalize causative conjugation is through repetition with verbs you actually use. Take the 20 or 30 verbs you use most often in Japanese and practice conjugating them into causative form. Say them out loud, write them down, make example sentences.

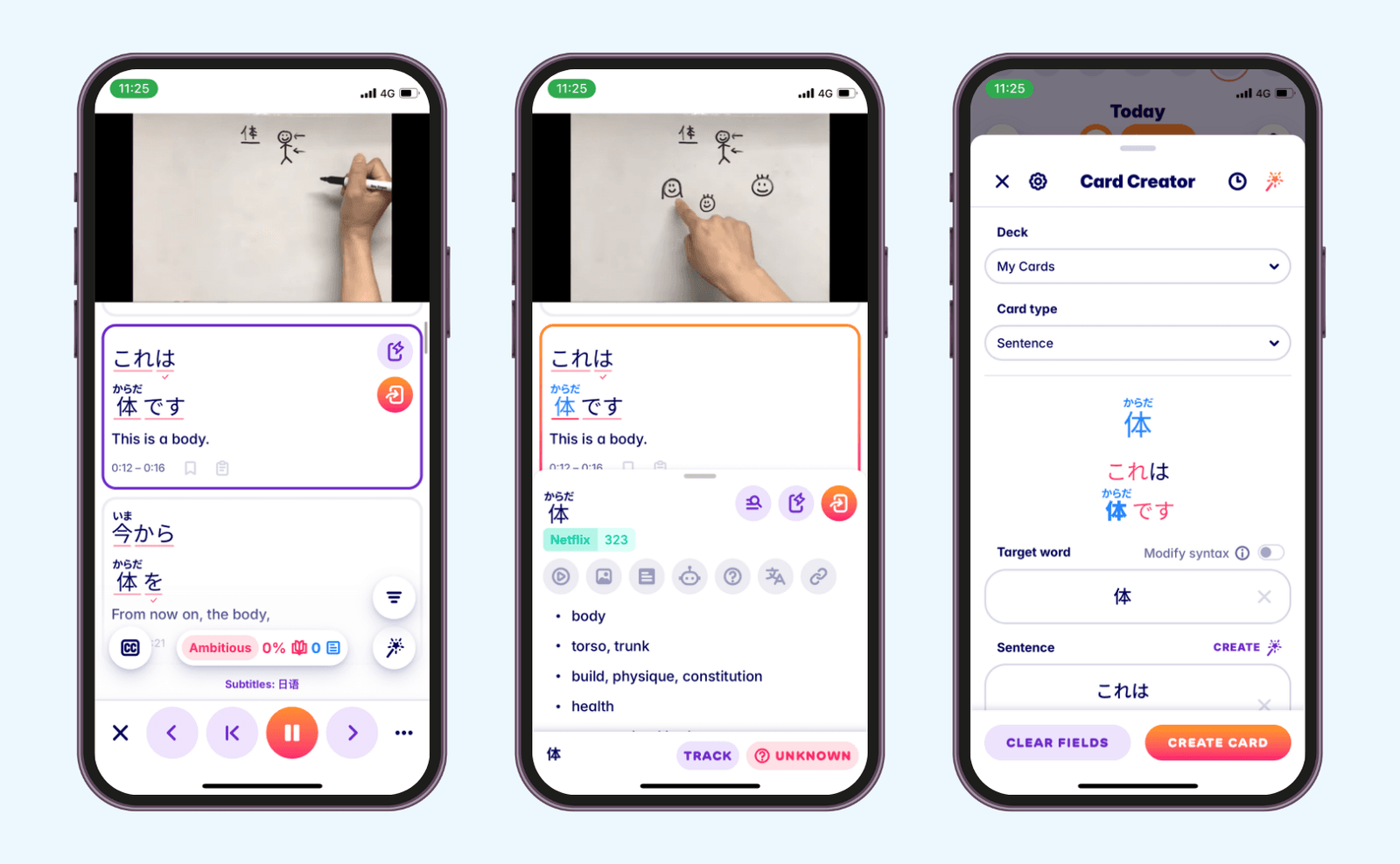

- Pay attention when you encounter causative verbs in native content. When you're watching anime or dramas, listen for those させる (saseru) endings. Notice which particles the speakers use. See how context determines whether it means "make" or "let."

- Try creating your own sentences about your daily life. What do you make people do? What do you let people do? What are you forced to do? Expressing your actual experiences helps the grammar stick way better than abstract textbook examples.

If you want to practice spotting causative forms in real Japanese content, Migaku's browser extension and app let you look up any verb instantly while watching shows or reading articles. You can see the conjugation breakdown and save examples to review later. There's a 10-day free trial if you want to check it out.

FAQs

Immerse yourself in daily Japanese content to learn causative and passive forms

First time learning this grammar? Everything looks strange. Your listening reaction to the causative sentences is slow, let alone using them with correct verb forms and particles when speaking. However, as you expose yourself to more native Japanese content, you will be able to recognize verbs in their different grammatical forms instantly.

If you consume media in Japanese, and you understand at least some of the messages and sentences within that media, you will make progress. Period.

The dreary acquisition phase will come to an end.