Japanese Conditional Form: Master と, たら, なら, 〜ば in Japanese Grammar

Last updated: January 18, 2026

How to say "if" when learning Japanese? Japanese has four main conditional forms, and they each handle different situations, which makes learning these Japanese conditionals feel way more complicated than it needs to be. But once you understand when to use each one, your Japanese sounds way more natural. I'm going to break down all four conditional forms in Japanese, show you how to conjugate them, and explain when you'd actually use each one. Pretty cool that one language has this many ways to express conditional statements, right?

- What are the 4 conditional forms

- と (To): The factual conditional

- ば (Ba): The general hypothetical conditional in Japanese grammar

- たら (Tara): The sequential conditional

- なら (Nara): The contextual conditional form in Japanese grammar

- Interchangeability and restrictions of the four ways to express conditional

- Tips for mastering Japanese conditionals

- FAQs

What are the 4 conditional forms

Japanese grammar includes four primary ways to express conditional statements. Each conditional form carries specific nuances that affect how native speakers interpret your sentence.

The four forms are:

- と (to) for natural consequences and factual conditions

- ば (ba) for general hypothetical situations

- たら (tara) for one-time events and sequential actions

- なら (nara) for contextual responses and specific situations

Learning these forms in Japanese helps you express exactly what kind of "if" you mean. The difference between these conditional structures matters way more than most textbooks let on.

と (To): The factual conditional

The と conditional form works for things that always happen. Think natural consequences, scientific facts, or habitual results. When A happens, B always follows.

Here's how you form it: Take the dictionary form of a verb and add と.

- (taberu) - to eat becomes (taberu to) - if/when you eat

- (iku) - to go becomes (iku to) - if/when you go

For i-adjectives, you just add と directly:

- (samui) - cold becomes (samui to) - if/when it's cold

Example sentences:

-

。

When spring comes, cherry blossoms bloom. (This happens every year. The conditional expresses an inevitable, factual result.) -

。

When you press this button, the light turns on. (This is a cause-and-effect relationship that happens every time.)

The と form has one major restriction: you can't use it with requests, commands, or expressions of will in the main clause. You can't say something like "If you go to the store, please buy milk" using と. That's where the other conditional forms come in.

ば (Ba): The general hypothetical conditional in Japanese grammar

The ば conditional form is used to express general hypothetical situations. This form appears in proverbs, general truths, and when you're talking about conditions that could apply broadly.

Conjugating verbs into the ば form takes a bit more work.

For u-verbs (Godan verbs), you change the final u-sound to the e-sound equivalent and add ば.

- (kaku) - to write becomes (kakeba) - if you write

- (yomu) - to read becomes (yomeba) - if you read

- (hanasu) - to speak becomes (hanaseba) - if you speak

For ru-verbs (Ichidan verbs), drop the る and add れば:

- (taberu) - to eat becomes (tabereba) - if you eat

- (miru) - to see becomes (mireba) - if you see

For i-adjectives, change the final い to ければ:

- (takai) - expensive becomes (takakereba) - if it's expensive

Example sentences:

-

。

If it's cheap, I'll buy it. -

。

If you study every day, you'll get good at it. -

。

If you're in a hurry, take the long way around. (Meaning: haste makes waste)

The ば form works great for general advice and hypothetical scenarios. You can use it with past tense in the main clause too, which gives you flexibility in expressing different time relationships.

たら (Tara): The sequential conditional

The たら conditional form handles one-time events, sequential actions, and past discoveries. This is probably the most versatile conditional in Japanese, and honestly, if you're not sure which one to use, たら is often a safe bet.

Forming たら is straightforward: take the past tense form of a verb and add ら.

- (tabeta) - ate becomes (tabetara) - if/when you eat

- (itta) - went becomes (ittara) - if/when you go

- した (shita) - did becomes したら (shitara) - if/when you do

For i-adjectives, change い to かったら:

- (takai) - expensive becomes (takakattara) - if it's expensive

Example sentences:

-

。

When you get home, please call me. (This shows a sequential action. First you get home, then you call.) -

。

If I won the lottery, I'd want to travel the world. (This is a hypothetical one-time event.) -

。

When I opened the door, there was a cat. (This describes a past discovery. You did one thing and discovered something as a result.)

The tara form is used to express both hypothetical situations and completed actions that led to discoveries. You can use it with requests, suggestions, and expressions of will in the main clause, which makes it way more flexible than と.

なら (Nara): The contextual conditional form in Japanese grammar

The なら conditional form responds to specific contexts or information. When someone tells you something and you want to respond based on that information, you use なら. This form is used when you're building on what someone else said or on a specific situation.

Forming なら is simple: add なら to the plain form of verbs, adjectives, or nouns.

- (iku) - to go becomes (iku nara) - if you're going

- (gakusei) - student becomes (gakusei nara) - if you're a student

Example sentences:

-

。

If you're going to Japan, I recommend Kyoto. (You're responding to the information that someone is going to Japan.) -

。

If it's tomorrow, I have time. (Someone asked about meeting up, and you're responding based on that specific context.) -

。

If it's him, he might know. (You're talking about a specific person in a specific context.)

The nara conditional works differently from the others because it focuses on the topic or context rather than a strict cause-and-effect relationship. You'll hear it all the time in conversations when people are responding to what was just said.

Interchangeability and restrictions of the four ways to express conditional

Here's where things get interesting. Sometimes you can swap these conditional forms around, and sometimes you absolutely cannot.

The と form has the strictest restrictions. You can't use it with:

- Commands or requests in the main clause

- Expressions of will or intention

- Suggestions or invitations

You can't say because that's a request. You need たら for that.

The ば form works for general hypothetical situations but sounds weird for one-time specific events. If you're talking about what happened yesterday when you opened the door, you'd use たら, not ば.

The たら form is the most flexible. You can use it in almost any conditional sentence, which is why beginners often overuse it. That's fine when you're learning, but as you advance, using the more specific forms makes you sound more natural.

The なら form only works when you're responding to context or building on information. You can't use it for general cause-and-effect relationships. It would sound strange to say because that's a natural fact, not a contextual response.

Some sentences accept multiple forms with slight nuance changes:

-

。

If I had money, I'd buy it. (General hypothetical) -

。

If I had money, I'd buy it. (More specific, one-time situation)

Both work, but ば sounds more like a general principle while たら feels more immediate and specific.

Tips for mastering Japanese conditionals

- Start by getting comfortable with たら since it's the most versatile. You can use it in most situations while you're still learning the nuances of the other forms.

- Pay attention to which form native speakers use in different contexts. Watch Japanese shows or read manga and notice when they use と for natural consequences, ば in proverbs or general advice, たら for specific situations, and なら when responding to context.

- Practice conjugating verbs into all four forms. Write out the conjugation patterns for common verbs until they become automatic. The conjugation itself isn't that hard once you drill it enough.

- Don't stress too much about getting it perfect when you're speaking. Native speakers will understand you even if you use たら where ば would sound more natural. The important thing is communicating your meaning, and you can refine your usage as you get more exposure to the language.

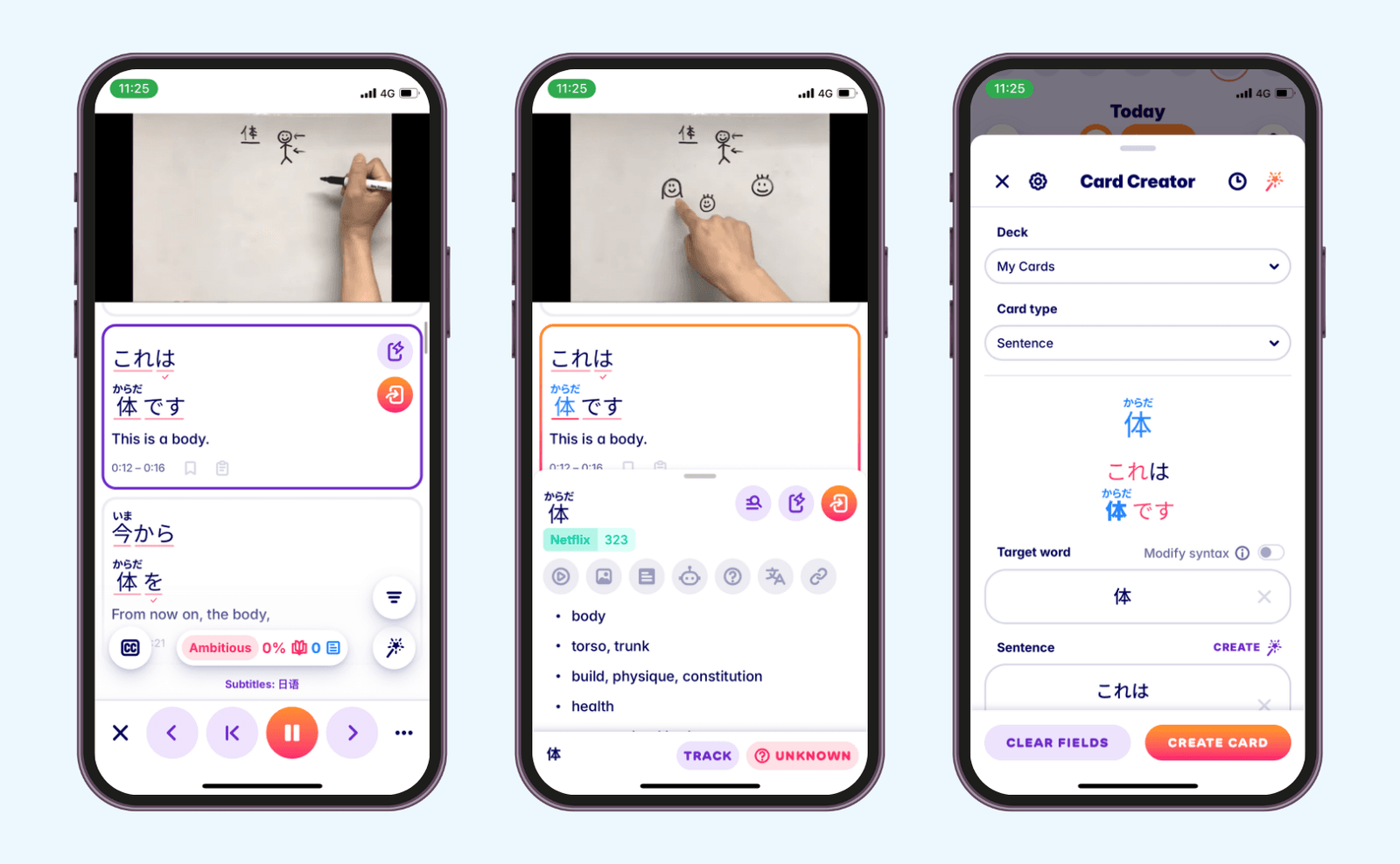

If you want to learn Japanese effectively, immersing yourself in real content makes a huge difference. Migaku's browser extension and app let you look up words and grammar patterns instantly while watching Japanese shows or reading articles, so you can see how these conditionals work in actual usage. There's a 10-day free trial if you want to check it out and start learning from native content right away.

FAQs

Build the mindset of Japanese conditional forms with extensive intake

Learning to use these forms in Japanese takes practice, but it's totally doable. Start with understanding the basic differences between the four forms, drill the conjugation patterns until they're automatic, and then pay attention to how native speakers use them in real contexts. Then, your way of thinking will be gradually adjusted to that.

If you consume media in Japanese, and you understand at least some of the messages and sentences within that media, you will make progress. Period.

Conditional forms are not hard, considering how often we're using them!