Japanese Name Order: Ways to Addressing Japanese People With Honorifics

Last updated: January 23, 2026

If you've ever watched anime or read manga, you've probably noticed something weird about how characters introduce themselves. They say their family name first, then their given name. This isn't just a quirky translation choice. Japanese name order actually works the opposite way from Western naming conventions, and understanding this is pretty essential if you're learning Japanese or planning to interact with Japanese people. Let's break down how Japanese names work, why the order matters, and how to avoid awkward situations when addressing people.

- How Japanese name order works

- Recent policy changes in 2020

- Understanding Japanese surnames

- How given names work

- Do Japanese people have middle names

- The honorific system you need to know

- Do Japanese go by first or last name

- Can non-Japanese people have Japanese names

- What about foreign name order in Japan

- Practical tips for learners addressing Japanese people

- FAQs

How Japanese name order works

The traditional Japanese name structure puts the family name first, followed by the given name.

So if you meet someone named Tanaka Yuki (), Tanaka is the surname and Yuki is the given name. This is the complete opposite of English naming conventions, where we say John Smith (Given name, then family name).

This family name-first pattern is actually common across East Asia. Chinese and Korean names follow the same structure. The logic behind this ordering reflects cultural values where family identity comes before individual identity. Your family name represents your lineage and family unit, which traditionally held more social significance than your individual identity.

Here's the thing: this traditional order gets confusing when Japanese names are written in English. For decades, many Japanese people reversed their names when introducing themselves to Westerners, putting their given name first to match English conventions. So Tanaka Yuki might introduce herself as "Yuki Tanaka" when speaking English. This created a ton of confusion about which name was actually which.

Recent policy changes in 2020

In 2020, the Japanese government started recommending that Japanese names be written in the traditional family name-first order even when using the Latin alphabet. By 2026, this has become increasingly standard in official documents, academic papers, and international communications. You'll see "TANAKA Yuki" (With the family name in all caps to make it clear) or "Tanaka Yuki" in official contexts now.

This policy shift means you need to pay attention to context when you see a Japanese name written in English. Is it following traditional order or Western order? Sometimes you can tell from capitalization, sometimes from context, and sometimes you just have to know the person's name already.

Understanding Japanese surnames

Japanese surnames typically come from geographic features, occupations, or historical clan names. Some of the most common family names include:

- Satou () - literally means "help wisteria"

- Suzuki () - means "bell tree"

- Takahashi () - means "high bridge"

- Tanaka () - means "middle of the rice field"

- Watanabe () - means "crossing area"

These five surnames alone account for millions of Japanese people. The meanings come from kanji characters, which are Chinese characters used in Japanese writing. Each kanji carries specific meanings, and surnames often reference natural features because historically, families took names based on where they lived or what the landscape looked like.

Japanese last names are almost always written with two kanji characters, though some use one or three. The pronunciation isn't always obvious from the kanji either. The same characters can sometimes be read different ways, which makes learning Japanese names pretty challenging.

How given names work

Given names in Japanese offer way more variety than surnames. Parents choose kanji characters based on the meanings they want to convey, the sound of the name, and sometimes current naming trends. Unlike surnames, given names can use one, two, or occasionally three kanji characters.

Gender plays a role in given names. Female given names often end in sounds like "ko" (), "mi" (), or "na" (). Male names frequently end in sounds like "ta" (), "ro" (), or "ki" (). But these are just tendencies, not hard rules.

Common male given names include:

- Hiroshi () - means "generous, tolerant"

- Takeshi () - means "military, warrior"

- Kenji () - means "healthy second son"

Common female given names include:

- Yuki ( or ) - can mean "reason, chronicle" or "snow" depending on kanji

- Sakura () - means "cherry blossom"

- Aiko () - means "love child"

Here's where it gets interesting: the same pronunciation can be written with completely different kanji, giving totally different meanings. Someone named Yuki might write it as (Snow), (Reason, chronicle), or (Gentleness, hope). This is why Japanese people often explain which kanji they use in their name.

Do Japanese people have middle names

Nope. The traditional Japanese naming system doesn't include middle names. You get a family name and a given name, that's it. Some Japanese people who spend significant time abroad or have international families might adopt middle names for convenience, but this isn't part of traditional Japanese culture.

This makes the structure pretty straightforward: family name plus given name equals your full name. No complicated multiple middle names like you sometimes see in Western countries.

The honorific system you need to know

Japanese people rarely use given names alone. The culture relies heavily on honorific suffixes attached to names to show respect and indicate relationships. This is where many Japanese learners mess up because English doesn't really have an equivalent system.

- San (さん) is the most common and safest honorific. Think of it as the equivalent of Mr., Ms., or Mrs., but way more versatile. You attach it to someone's family name: Tanaka-san (). You can use san with almost anyone in almost any situation. It works for colleagues, acquaintances, store clerks, basically anyone you want to be polite toward.

- Sama (様) is a more formal, respectful version of san. You'd use this for customers, people of much higher status, or in very formal business situations. It shows serious respect.

- Kun (君) is typically used for boys or young men, often by someone older or of higher status. Teachers might call male students by their family name plus kun: Tanaka-kun (). It can also be used between male friends or colleagues of equal status.

- Chan (ちゃん) is an affectionate, informal honorific usually used for children, close female friends, or sometimes pets. It sounds cute and familiar. You'd never use chan in a business setting or with someone you just met.

- Sensei (先生) means "teacher" but gets used as an honorific for teachers, doctors, lawyers, artists, and other professionals. You attach it directly to their family name: Tanaka-sensei ().

Do Japanese go by first or last name

Japanese people typically go by their family name in most social situations.

When you meet someone new, you'd address them by their surname plus an appropriate honorific. So if you meet Tanaka Yuki at work, you'd call her Tanaka-san (), not Yuki-san.

Using someone's given name implies a close personal relationship.

You generally need explicit permission to switch from family name to given name. This is a big deal in Japanese culture. Calling someone by their given name without that level of familiarity comes across as either weirdly intimate or disrespectful.

Close friends, family members, and romantic partners use given names. Sometimes they'll add chan for affection. But even longtime colleagues might stick with family names plus san for their entire careers.

There are exceptions. In some modern workplaces, especially international companies or creative industries, people might use given names more freely. Some younger Japanese people prefer given name usage among friends. But the default is still family name plus honorific.

Can non-Japanese people have Japanese names

Foreigners living in Japan or studying Japanese sometimes wonder about adopting Japanese names. Here's the reality: you can choose a Japanese name for everyday use, but legally changing your name to a Japanese name as a non-citizen is complicated.

Many foreigners who work in Japan or study there long-term pick a Japanese name that approximates their real name's sound. Someone named Sarah might use Sara (), which sounds similar. This makes daily life easier since Japanese pronunciation struggles with certain foreign sounds.

If you become a naturalized Japanese citizen, you can legally take a Japanese name. You'd choose a family name and given name using kanji characters. But as a foreigner just visiting or working in Japan, you'll typically keep your original name and have it written in katakana (the Japanese script used for foreign words).

Your passport name stays the same regardless. The Japanese name would be for daily use, business cards, or social situations.

What about foreign name order in Japan

When Japanese people write or say foreign names, they typically use the original name order.

So "John Smith" stays "John Smith" (ジョン・スミス in katakana), not "Smith John." This sometimes creates confusion because Japanese names get reversed in English, but foreign names stay in original order in Japanese.

The pronunciation of foreign names in Japanese can sound pretty different from the original. Japanese phonetics don't include certain sounds that exist in English and other languages, so names get adapted. "Smith" becomes "Sumisu" (スミス), "Robert" becomes "Robaato" (ロバート). The katakana writing system approximates foreign sounds as closely as possible within Japanese phonetic constraints.

Practical tips for learners addressing Japanese people

If you're learning Japanese or planning to interact with many Japanese people, here's what actually helps:

- Start with family names plus san. This works in basically every situation until someone tells you otherwise. When in doubt, err on the side of formality.

- Pay attention to how Japanese people introduce themselves. The first name they say is their family name (in Japanese contexts). Listen for the order and mirror it.

- Don't assume you can use someone's given name just because you've met a few times. Wait for explicit permission or very clear social cues that you've reached that level of friendship.

- Learn the basic honorifics (san, kun, chan, sensei) and when to use each. This matters way more than memorizing whether someone's name is first or last.

- If you're writing about Japanese people in English, decide on a consistent approach. Either use traditional order throughout (Family name first) or Western order throughout (Given name first). Just be consistent and consider adding a note explaining which convention you're using.

- Remember that names are written in kanji, and the meaning matters to Japanese people. If someone explains the kanji in their name, that's them sharing something meaningful about their identity. Show interest.

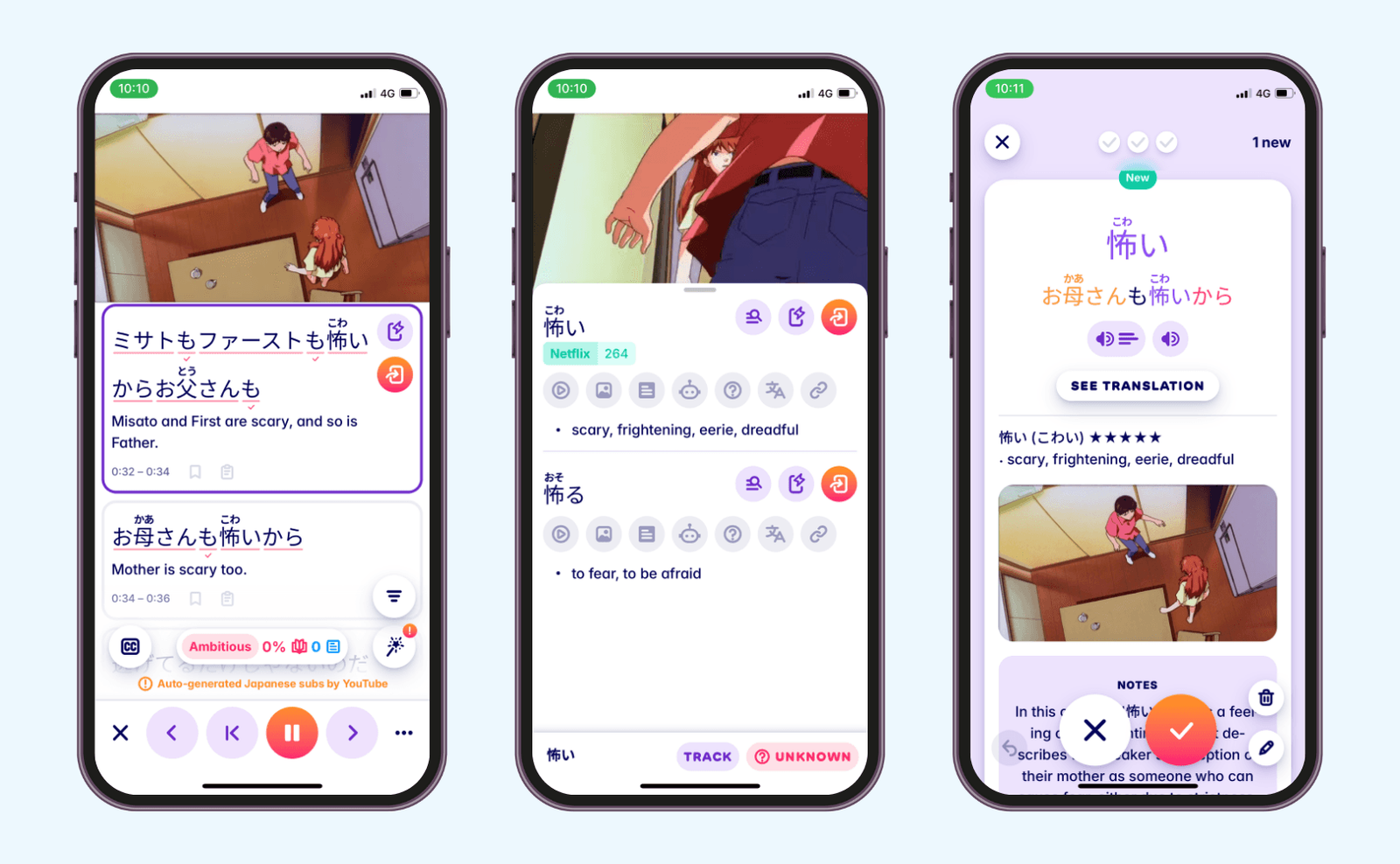

Anyway, if you're serious about learning Japanese, Migaku's browser extension and app let you look up kanji and vocabulary instantly while watching Japanese shows or reading articles. Makes learning name kanji and other vocabulary way more practical when you see them in real context. There's a 10-day free trial if you want to check it out.

FAQs

Knowing the order of Japanese names matters beyond just being polite

Understanding Japanese name order goes deeper than avoiding social awkwardness. It reflects fundamental cultural values about family, hierarchy, and social relationships. As you consume more Japanese content, you will gradually accumulate the most common Japanese given and family names.

If you consume media in Japanese, and you understand at least some of the messages and sentences within that media, you will make progress. Period.

Good at remembering names is a big plus in making new friends!