Reading Japanese Literature: Know the History of Japanese Literature and How to Read Japanese Works

Last updated: January 26, 2026

Reading Japanese literature opens up an entire world of storytelling that feels completely different from Western narratives. The pacing, the emotional subtlety, the way characters think and interact, it all reflects centuries of unique cultural development. This guide walks you through the actual process of building reading ability when learning Japanese, from your first hiragana character to tackling full novels.

- Starting with the basics: hiragana and katakana

- Understanding kanji without losing your mind

- Your first reading materials: graded readers and simple texts

- Tools that actually help: SRS and digital reading aids

- The progression roadmap: from simple to sophisticated

- Diving into the classic Japanese literature and great Japanese novels

- The four types of Japanese literature

- How Japanese literature reflects culture and history

- Literature in translation versus original Japanese

- Building reading stamina and speed when reading Japanese novels

Starting with the basics: hiragana and katakana

You cannot read Japanese literature without mastering the two phonetic scripts first. Hiragana (ひらがな) and katakana (カタカナ) form the foundation of everything you'll read.

- Hiragana handles native Japanese words and grammatical particles,

- while katakana represents foreign loanwords and emphasis.

The good news? These scripts are pretty straightforward. Hiragana has 46 basic characters, and katakana has the same number. Most learners can memorize both within two to three weeks of consistent practice.

Start with hiragana first. Focus on recognition before production, meaning you should be able to read the characters fluently before worrying about writing them perfectly. Use mnemonics for tricky characters. For example, nu (ぬ) looks like a noodle, and me (め) looks like an eye (which is what "me" means in Japanese).

Once you've got hiragana down, move to katakana. The challenge here is that many katakana characters look similar to hiragana but represent different sounds. Shi (シ) in katakana looks like tsu (つ) in hiragana. So (ソ) looks like n (ん). Practice distinguishing these pairs specifically.

Don't spend months on these scripts. Two to four weeks max, then move forward. You'll continue reinforcing them through actual reading practice.

Understanding kanji without losing your mind

Kanji () are the Chinese characters used in Japanese writing, and they're where most learners hit a wall. There are roughly 2,000 kanji in regular use (the jouyou kanji or set), and literature often includes more obscure characters beyond that.

Here's what actually works: learn kanji through vocabulary, not in isolation. Studying the character for "eat" () makes way more sense when you learn it through words like taberu (, to eat) and shokuji (, meal).

Focus on radicals (, bushu), the building blocks of kanji. Each kanji is made up of components that often hint at meaning or pronunciation. The character (Language) contains the radical (Speech/Words) on the left. Once you recognize common radicals like 氵(Water), (Tree), and (Person), kanji stop looking like random scribbles and start making logical sense.

Aim for about 10 to 15 new kanji per day through vocabulary study. This pace gets you to basic literacy (Around 1,000 kanji) in three to four months. For reading literature, you'll eventually want to know 1,500 to 2,000 kanji, which takes most learners six months to a year of consistent study.

Your first reading materials: graded readers and simple texts

Once you know hiragana, katakana, and maybe 300 to 500 kanji, you can start reading actual Japanese. But jumping straight into Japanese novels would be brutal and demotivating.

Graded readers are texts specifically written for learners, with controlled vocabulary and grammar. They're organized by level, typically from N5 (Beginner) to N2 (Upper intermediate) following the JLPT (Japanese Language Proficiency Test) system.

Start with readers that include furigana (ふりがな), the small hiragana characters printed above kanji to show pronunciation. This lets you read without constantly stopping to look up characters. As you progress, gradually move to texts with less furigana support.

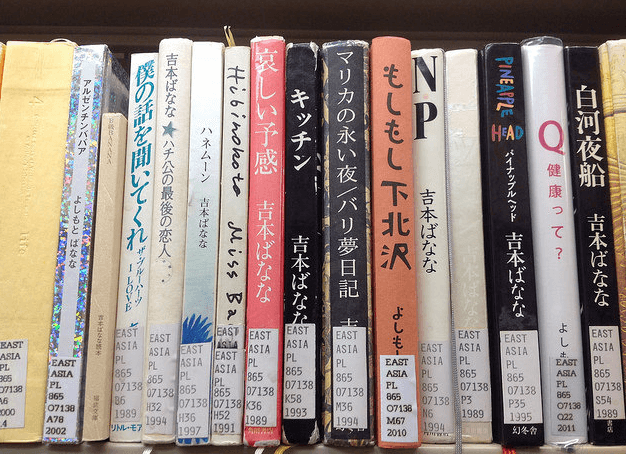

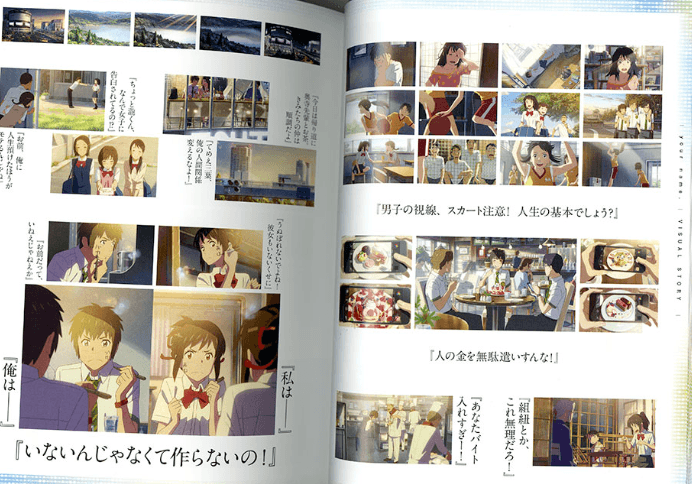

Light novels (ライトノベル, raito noberu) bridge the gap between graded readers and regular literature. These young adult novels use simpler language than literary fiction, often include some furigana, and feature conversational dialogue. Popular series like "Kimi no Na wa" (, Your Name) or "Kino no Tabi" (, Kino's Journey) work well for intermediate learners.

Manga represents another excellent stepping stone. The combination of images and text provides context clues, and dialogue-heavy manga expose you to natural conversation patterns. Slice-of-life genres like "Yotsuba to!" (よつばと!) use everyday vocabulary that transfers directly to other reading.

Tools that actually help: SRS and digital reading aids

- Spaced Repetition Systems (SRS) like Anki make vocabulary stick in long-term memory. Instead of cramming words and forgetting them next week, SRS apps schedule reviews at optimal intervals based on how well you remember each item.

- Create vocabulary cards from your reading. When you encounter a new word in context, add it to your deck with the sentence where you found it. This contextual learning beats memorizing isolated word lists by a huge margin.

- Digital reading tools transform the learning process. E-readers and apps let you tap words for instant definitions. Browser extensions like Migaku extension can overlay translations or furigana on Japanese websites. These tools remove the friction of constant dictionary lookups, letting you maintain reading flow while still learning new vocabulary.

The progression roadmap: from simple to sophisticated

Reading ability develops in stages. Here's a realistic timeline:

- Months 1 to 3: Master hiragana and katakana completely. Learn 500 to 800 basic kanji through vocabulary. Read graded readers at N5 and N4 levels. Your reading speed will be painfully slow, maybe 5 to 10 minutes per page.

- Months 4 to 6: Expand to 1,000 to 1,200 kanji. Move to N3-level graded readers and simple light novels. Start reading manga in Japanese. Reading speed improves to 2 to 5 minutes per page for appropriate-level material.

- Months 7 to 12: Push toward 1,500 to 2,000 kanji. Tackle full light novels and easier contemporary novels. Reading speed for comfortable material reaches 1 to 2 minutes per page.

- Year 2 and beyond: Approach native-level reading with 2,000+ kanji. Start exploring classic Japanese literature from different periods. Reading speed for contemporary novels approaches native pace (30 to 60 pages per hour).

These timelines assume consistent daily practice, maybe 30 to 60 minutes of reading plus 20 to 30 minutes of vocabulary review.

Diving into the classic Japanese literature and great Japanese novels

Once you've built a foundational reading ability, you can approach the classic Japanese literature. The landscape spans over a thousand years of writing, from ancient poetry to contemporary fiction.

Heian period

The Heian period (794 to 1185) produced some of Japan's most celebrated works. "Genji Monogatari" (, The Tale of Genji) by Murasaki Shikibu, written between 1001 - 1008, is often called the world's first novel. The classical Japanese used in Heian literature differs significantly from modern Japanese, so these texts remain challenging even for advanced learners without specialized study.

Meiji period

The Meiji period (1868 to 1912) marks when Japanese literature began incorporating Western influences. Writers like Natsume Souseki () and Mori Ougai () created works that blended Japanese sensibilities with European literary techniques. Natsume's work "Kokoro" (こころ, Heart) remains one of the most famous Japanese novels, examining friendship, betrayal, and isolation.

20th-century literature authors and works

In the 20th century, Japan saw massive changes. Early Showa period writers explored social realism and psychological depth. Post-war authors processed the trauma of World War II and rapid modernization. Writers like Kawabata Yasunari () and Mishima Yukio () gained international recognition with famous piece such as (Snow Country), (The Sea of Fertility).

Modern Japanese fictions

Contemporary authors like Murakami Haruki () write in relatively accessible modern Japanese, making them popular choices for intermediate learners. His novels use straightforward sentence structures and everyday vocabulary compared to more literary writers.

The four types of Japanese literature

Japanese literature traditionally divides into four main categories, though modern works often blur these boundaries:

- Poetry includes forms like tanka (, 31-syllable poems) and haiku (, 17-syllable poems). Classical poetry anthologies like "Manyoushuu" (, Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves) from the 8th century established poetic traditions that continue today.

- Prose narratives encompass novels, short stories, and longer fictional works. This category includes everything from Heian period tales to contemporary fiction.

- Drama covers theatrical forms like nou (, classical musical drama), kabuki (, stylized dance-drama), and modern plays. These texts combine dialogue with stage directions and often include specialized vocabulary.

- Essays and diaries form a distinct literary tradition in Japan. "Makura no Soushi" (, The Pillow Book) by Sei Shonagon, written around 1000 CE, exemplifies the zuihitsu (, miscellaneous writings) genre that remains popular.

For learners, prose narratives and contemporary essays provide the most accessible entry points. Poetry requires deep cultural knowledge to be appreciated fully, and drama texts assume familiarity with performance contexts.

How Japanese literature reflects culture and history

Reading Japanese literature in the original language reveals cultural nuances that disappear in translation. The language itself encodes social relationships through different levels of politeness and formality. When a character switches from casual to formal speech, it signals changing power dynamics or emotional distance.

Mono no aware (), the awareness of impermanence and the bittersweet nature of life, runs through Japanese literature across centuries. This aesthetic principle shapes how characters respond to loss, change, and beauty. You'll notice it in the cherry blossom imagery that appears constantly, symbolizing both beauty and transience.

Historical periods directly influenced literary themes and styles:

- Heian period literature focused on court life and romantic relationships.

- Edo period (1603 to 1868) literature explored merchant culture and urban life.

- Post-war literature grappled with defeat, occupation, and rapid social change.

- Contemporary literature reflects modern Japan's relationship with technology, global culture, and shifting social norms.

Reading these works in Japanese lets you see how the language itself evolves, incorporating new vocabulary and changing usage patterns.

Literature in translation versus original Japanese

Reading Japanese literature in English translation serves a different purpose than reading in Japanese. Translations let you experience the stories, themes, and characters without years of language study. Great translators like Edward Seidensticker and Jay Rubin have made Japanese literature accessible worldwide.

But translation always involves compromise:

- Wordplay disappears.

- Cultural references get footnoted or simplified.

- The rhythm and sound of the original language vanishes completely.

- Honorifics and speech levels get flattened into English equivalents that miss the original nuance.

Reading in Japanese, even with a dictionary beside you, connects you directly to the author's choices. You notice repeated words that create thematic links. You hear the difference between characters' speech patterns. You catch cultural references that wouldn't make sense to translate.

For learners, the goal should be reading both. Use translations to discover authors and works you enjoy, then challenge yourself to read excerpts or full works in Japanese as your ability grows.

Building reading stamina and speed when reading Japanese novels

Early on, reading Japanese feels exhausting. Looking up every third word, parsing unfamiliar grammar, decoding kanji, it all drains mental energy fast. You might manage 10 to 15 minutes before your brain refuses to process more.

Reading stamina builds gradually through consistent practice.

- Start with short sessions, maybe 10 to 20 minutes daily. As your vocabulary grows and grammar patterns become automatic, you'll naturally read longer without fatigue.

- Reading speed improves through volume. The first novel takes forever. The tenth novel in the same genre goes much faster because you've internalized common vocabulary and phrasing. Genre reading helps here: if you read several mystery novels, you'll quickly learn crime-related vocabulary that appears across the genre.

- Don't obsess over understanding every single word. Aim for comprehension of main ideas and plot, looking up only words that appear frequently or seem crucial to meaning. This extensive reading approach builds fluency faster than intensive study of every sentence.

- Connect with other learners or native speakers to discuss what you're reading. Online book clubs, language exchange partners, or study groups add social motivation and deepen comprehension through discussion.

Anyway, if you want to actually tackle Japanese literature with real support, Migaku's browser extension and app let you look up words instantly while reading Japanese websites, news, or web novels. The instant definitions and Anki integration make reading practice way more efficient. There's a 10-day free trial if you want to check it out.

Start reading with English translation is not a bad idea

Every learner needs to start somewhere, especially using a method that makes them feel it is manageable. While graded readers can come in handy, the content might be boring for someone who craves engaging and interesting stories. Then, why not read the book with an English translation first? Get a grip on the main plot and characters, then switch to reading the work without the translation. This method also allows you to appreciate the Japanese choices of words better!

If you consume media in Japanese, and you understand at least some of the messages and sentences within that media, you will make progress. Period.

Make the first step bravely!