French Articles Guide: Le, La, Les, Un, Une, Des in French Grammar Explained

Last updated: February 13, 2026

Articles can feel like a puzzle when you're just starting out learning French. You've got le, la, les, un, une, des, and then du and de la thrown in for good measure. The thing is, once you understand the basic patterns behind these little words, they actually make a lot of sense. This French articles guide breaks down all three types (Definite, indefinite, and partitive) with clear examples so you can finally stop second-guessing yourself every time you need to say "the" or "a" in French.

- Why French articles matter more than you think

- French definite articles: le, la, l', les

- Indefinite articles in French: un, une, des

- French partitive articles: du, de la, de l', des

- Gender and number agreement with articles

- Contractions with prepositions

- Common mistakes to avoid in French uses of articles

Why French articles matter more than you think

Articles are the most common French determiners, but did you know that there are many other kinds? Possessive determiners like "mon" and "ma", demonstrative determiners like "ce" and "cette", they all exist. But articles come first because you'll use them in practically every sentence you speak or write.

Here's the thing about French articles: they do more work than English articles. In English, "the" is just "the" regardless of what comes after it. In French, the definite article changes based on the gender and number of the noun it precedes. Same goes for indefinite and partitive articles. This means you're constantly communicating information about whether something is masculine, feminine, singular, or plural just through your choice of article.

Getting comfortable with articles early on makes everything else in French grammar easier. Once you internalize these patterns, you'll naturally absorb noun genders as you learn new vocabulary.

French definite articles: le, la, l', les

The definite article in French works like "the" in English. You use it when talking about specific things or when both you and your listener know exactly what you're referring to.

The basic forms

French has four forms of the definite article:

- le: Masculine singular (le chat = the cat)

- la: Feminine singular (la table = the table)

- l': Masculine or feminine singular before a vowel or silent h (l'ami = the friend, l'heure = the hour)

- les: Masculine or feminine plural (les chats = the cats, les tables = the tables)

The tricky part is remembering that every single noun in French has a gender. There's no logic to most of it. A table is feminine, a book is masculine. You just have to learn the gender along with the noun itself.

When vowels get involved

When a noun starts with a vowel sound or a silent h, both le and la become l'. This is called elision, and it happens to make pronunciation smoother. Instead of saying "le ami" with that awkward pause, you say "l'ami" as one fluid sound.

The catch is figuring out whether that noun is masculine or feminine, since l' doesn't tell you. L'arbre is masculine (Tree), but l'eau is feminine (Water). You need to memorize the gender separately or pick it up from context.

Using definite articles differently from English

French uses the definite article in some situations where English doesn't. When you're talking about things in a general sense, French requires the article:

- J'aime le chocolat

I like chocolate - La vie est belle

Life is beautiful - Les chiens sont fidèles

Dogs are loyal

In English, we'd just say "I like chocolate" without "the", but French needs that definite article to make the sentence grammatically correct.

Indefinite articles in French: un, une, des

The indefinite article works like "a" or "an" in English. You use it when referring to non-specific items or introducing something for the first time.

The three forms

French has three indefinite articles:

- un: Masculine singular (un livre = a book)

- une: Feminine singular (une pomme = an apple)

- des: Masculine or feminine plural (des livres = books, des pommes = apples)

That plural form "des" is interesting because English doesn't really have a plural indefinite article. We just say "books" or "some books", but French always needs "des" in front.

Counting and quantities

When you're talking about a specific number, you drop the indefinite article:

- J'ai trois livres

I have three books - Elle a acheté cinq pommes

She bought five apples

But when the quantity is vague or you're just mentioning that plural items exist, you need des:

- J'ai des livres

I have some books - Il y a des pommes sur la table

There are apples on the table

After negation

Here's something that trips people up: after a negative construction, un, une, and des usually become de or d':

- J'ai un chat

I have a cat - Je n'ai pas de chat

I don't have a cat - Elle a des amis

She has friends - Elle n'a pas d'amis

She doesn't have friends

This rule has exceptions, particularly when you're emphasizing the noun or making a philosophical statement, but for everyday conversation, just remember that negation changes indefinite articles to de.

French partitive articles: du, de la, de l', des

The partitive article is where things get really different from English. We don't have a direct equivalent, which is why this concept takes a while to sink in.

What partitive means

Partitive articles express an unspecified quantity of something. You use them with uncountable nouns or when you're talking about part of a whole rather than a complete, countable item.

The forms are:

- du: Masculine singular (du pain = some bread)

- de la: Feminine singular (de la confiture = some jam)

- de l': Masculine or feminine singular before vowel (de l'eau = some water)

- des: Masculine or feminine plural (des épinards = some spinach)

Wait, des appears in both indefinite and partitive? Yep. Context tells you which one it is.

When to use partitive articles in French

You'll use the partitive with food and drink items most commonly:

- Je mange du fromage

I'm eating cheese - Elle boit de la limonade

She's drinking lemonade - Nous avons de l'argent

We have money

Think of it this way: you're not eating "a cheese" as a whole unit, you're eating some amount of cheese. You're not drinking "a lemonade" necessarily, you're drinking some lemonade.

Partitive versus definite with food

This confuses a lot of learners. Sometimes you use the partitive with food, sometimes the definite article. The difference is whether you're talking about a specific portion you're consuming right now (Partitive) or making a general statement about the food itself (Definite):

- J'aime le fromage

I like cheese (in general) (Definite article) - Je mange du fromage

I'm eating some cheese (right now) (Partitive article)

The question "Avez-vous bu du thé?" uses the partitive because it's asking if you drank some tea, a portion of tea, not whether you like tea as a concept.

Partitive in negative sentences

Just like indefinite articles, partitive articles become de or d' after negation:

- J'ai du temps

I have time - Je n'ai pas de temps

I don't have time - Elle boit de la bière

She drinks beer - Elle ne boit pas de bière

She doesn't drink beer

Partitive with expressions of quantity

When you use expressions of quantity like "beaucoup de" (A lot of), "un peu de" (A little of), or "trop de" (Too much of), you drop the partitive article:

- Je bois beaucoup de café

I drink a lot of coffee - Elle a un peu d'argent

She has a little money

The "de" is already built into these expressions, so you don't need du, de la, or des.

Gender and number agreement with articles

Every noun in French has a gender (Masculine or feminine) and a number (Singular or plural). Your article choice must match both.

This is why learning French means memorizing noun genders from day one. When you learn a new word, learn it with its article: "le chat", "la maison", "l'arbre". Don't just memorize "chat" by itself.

Some patterns can help. Nouns ending in -tion are usually feminine (la nation, la solution). Nouns ending in -age are usually masculine (le garage, le fromage). But these are guidelines with plenty of exceptions, so don't rely on them completely.

For plural forms, the article changes to les (Definite) or des (Indefinite/Partitive), regardless of gender. That's one thing that gets easier in plural.

Contractions with prepositions

When certain prepositions meet articles, they contract into single words. The preposition à (to, at) combines with le and les:

- à + le = au (Je vais au marché = I'm going to the market)

- à + les = aux (Je parle aux enfants = I'm talking to the children)

But à doesn't contract with la or l':

- Je vais à la plage (I'm going to the beach)

- Je pense à l'avenir (I'm thinking about the future)

The preposition de (of, from) also contracts:

- de + le = du (Je viens du Canada = I come from Canada)

- de + les = des (Je parle des films = I'm talking about the films)

Again, no contraction with la or l':

- Je viens de la France (I come from France)

- Je parle de l'école (I'm talking about the school)

This creates some confusion because "du" and "des" appear as both partitive articles AND as contracted prepositions. You figure out which one from context.

Common mistakes to avoid in French uses of articles

One mistake I see constantly: using the wrong article before a vowel. People forget that both le and la become l', so they'll say something like "le ami" instead of "l'ami". Your ear will catch this once you've heard enough French, but early on you have to consciously remember the rule.

Another issue: forgetting articles entirely. In some languages, you can drop articles in certain contexts. In French, almost every noun needs an article (or another determiner). "J'ai chat" is wrong. It has to be "J'ai un chat" or "J'ai le chat", depending on what you mean.

Mixing up definite and partitive with food is super common. "J'aime du chocolat" sounds wrong to native speakers. It should be "J'aime le chocolat" because you're making a general statement about chocolate, not consuming some right now.

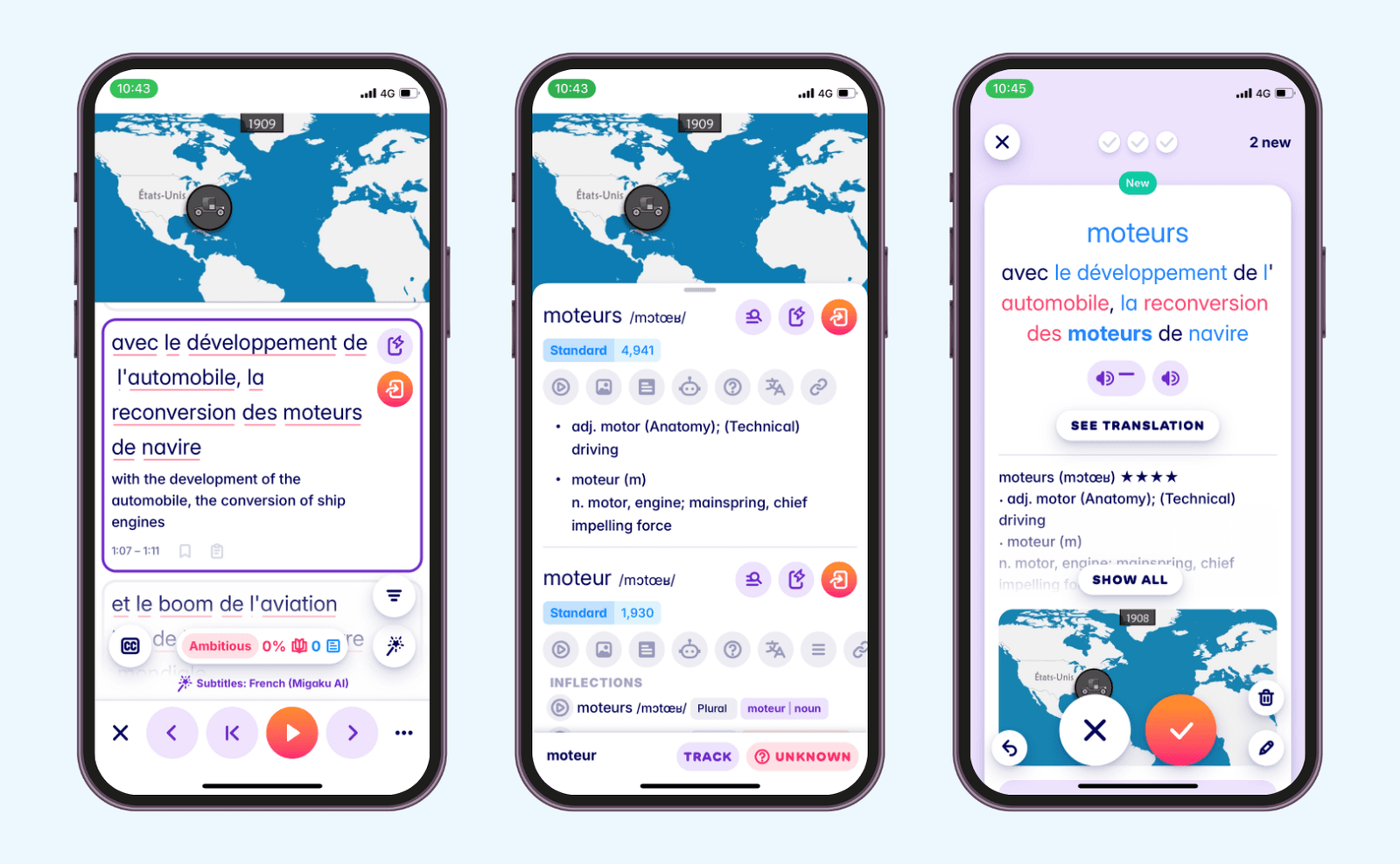

Of course, you can't avoid all the mistakes, and language learning can be difficult. Migaku helps you learn French through real content like shows, movies, and articles. You can look up any word instantly while reading or watching, and the app automatically creates flashcards from the vocabulary you encounter. There's a 10-day free trial if you want to see how immersion learning with actual support tools makes this whole process way faster.

Textbooks can't help you master French articles in nuanced situations

Once you're comfortable with the core article in French usage, you'll start noticing more nuanced situations. Sometimes articles are omitted after certain expressions (avoir faim = to be hungry, without an article before faim). Sometimes the choice of article changes the meaning subtly. You'll also encounter situations where multiple articles could technically work, but one sounds more natural than another. This level of fluency comes from exposure to authentic French content over time.

If you consume media in French, and you understand at least some of the messages and sentences within that media, you will make progress. Period.

Keep on going, even when the going gets tough!🏃🏻♀️➡️