Portuguese Sentence Structure: Basic Guide for Language Learning Beginners

Last updated: February 6, 2026

Learning Portuguese sentence structure feels way less intimidating once you realize it follows pretty much the same basic pattern as English. If you can form a sentence in English, you're already halfway there with Portuguese. The real trick is understanding a few key differences in how verbs work, where adjectives go, and how Portuguese speakers form questions without flipping the word order around. Let's break down the essentials so you can start building your own sentences right away.

- The basic SVO structure in Portuguese

- How Portuguese verbs change everything

- Working with nouns and adjectives

- Forming negative sentences with não

- How questions work in Portuguese

- Using interrogative words

- Understanding linking verbs and transitive verbs

- Where adverbs fit in

- Pronouns and possessive forms

- Practical sentence building examples

- Brazilian Portuguese versus European Portuguese

- Common mistakes to avoid

The basic SVO structure in Portuguese

Portuguese uses an SVO structure, which means Subject-Verb-Object.

This is the exact same pattern English follows, so you've got a massive head start here. Here's what that looks like:

- Subject: who or what does the action

- Verb: the action itself

- Object: who or what receives the action

A simple example: "Maria come pão" (Maria eats bread). Maria is the subject, come is the verb, and pão is the object. Pretty straightforward, right?

Let's look at a few more examples:

- O gato bebe água

The cat drinks water - João lê livros

João reads books - Nós falamos português

We speak Portuguese

The word order stays consistent across these sentences. You'll find this pattern everywhere in both Brazilian Portuguese and European Portuguese, making it one of the most reliable rules you can count on.

How Portuguese verbs change everything

Here's the thing about Portuguese verbs: they conjugate based on who's doing the action.

Unlike English where you mostly just add an 's' for third person, Portuguese verbs change their endings for each pronoun.

Let's take the verb "falar" (To speak):

- Eu falo (I speak)

- Você fala (You speak)

- Ele/ela fala (He/she speaks)

- Nós falamos (We speak)

- Vocês falam (You all speak)

- Eles/elas falam (They speak)

Notice how the verb ending changes each time? This is called conjugation, and it happens with every verb in Portuguese.

The tense also affects how the verb looks. "Eu falo" means "I speak" in present tense, but "eu falei" means "I spoke" in past tense.

Because the verb ending tells you who's doing the action, Portuguese speakers often drop the subject pronoun entirely. You'll hear "Falo português" instead of "Eu falo português" all the time. Both mean "I speak Portuguese," but the first version sounds more natural in everyday conversation.

This subject omission happens constantly in Portuguese. The sentence "Comemos pizza" (We eat pizza) works perfectly fine without "nós" at the beginning because the verb ending "emos" already tells you it's "we" doing the action.

Working with nouns and adjectives

Portuguese handles adjectives differently than English, and this trips up a lot of beginners.

Most adjectives come after the noun instead of before it.

In English, you say "the red car." In Portuguese, you say "o carro vermelho" (The car red). The adjective "vermelho" follows the noun "carro."

More examples:

- "A casa grande" (The big house, literally "the house big")

- "O livro interessante" (The interesting book)

- "Uma pessoa legal" (A nice person)

But wait, some common adjectives actually do go before the noun. Words like "bom" (Good), "mau" (Bad), "grande" (Big), and "pequeno" (Small) often appear before the noun:

- "Um bom dia" (A good day)

- "Uma grande cidade" (A big city)

Adjectives also need to match the noun in gender and number.

If the noun is feminine, the adjective becomes feminine. If it's plural, the adjective becomes plural too.

- "O gato preto" (The black cat, masculine)

- "A gata preta" (The black cat, feminine)

- "Os gatos pretos" (The black cats, masculine plural)

Forming negative sentences with não

Making a sentence negative in Portuguese is super simple.

Just stick "não " right before the verb. That's it.

- Eu não falo português

I don't speak Portuguese - Ela não come carne

She doesn't eat meat - Nós não entendemos

We don't understand - Eles não trabalham aqui

They don't work here

The word order stays exactly the same as the positive sentence. You're just adding "não" before the verb. No complicated auxiliary verbs like "don't" or "doesn't" to worry about.

You can also use double negatives in Portuguese, which actually strengthens the negation rather than canceling it out:

- Não tenho nada

I don't have anything - Não vejo ninguém

I don't see anyone

How questions work in Portuguese

This is where Portuguese gets really interesting. Unlike English, you don't flip the subject and verb around to form a question. The word order stays exactly the same.

The statement "Você fala inglês" (You speak English) becomes a question just by changing your intonation: "Você fala inglês?" The only difference is your voice goes up at the end.

In Brazilian Portuguese especially, people form questions by keeping the exact same sentence structure and just raising their pitch. This feels weird at first if you're used to English, but it's how most questions work in everyday conversation.

Compare these:

- Ela está em casa

She is at home - Ela está em casa?

Is she at home?

Same words, same order, different intonation. Pretty cool!

Using interrogative words

When you need to ask specific questions using words like "what," "where," or "when," Portuguese uses interrogative words at the beginning of the sentence. The rest of the sentence keeps its normal structure.

Common interrogative words:

Portuguese | English |

|---|---|

Que / O que | What |

Onde | Where |

Quando | When |

Por que / Por quê | Why |

Como | How |

Quem | Who |

Quanto | How much/many |

Examples:

- O que você quer?

What do you want? - Onde ela mora?

Where does she live? - Como você está?

How are you? - Quando eles chegam?

When do they arrive?

Notice the verb still comes after the subject. You're not saying "What do you want?" with the auxiliary "do" like in English. The Portuguese version translates more literally to "What you want?"

Here's something that confuses people: "Como você está?" means "How are you?" (Asking about your temporary state), while "Como você é?" means "What are you like?" (Asking about your personality or characteristics). The verb changes the meaning completely.

Understanding linking verbs and transitive verbs

Portuguese uses linking verbs to connect the subject to a description.

The verb "ser " (To be) is the most common linking verb:

- Eu sou professor

I am a teacher - Ela é inteligente

She is intelligent

The verb "estar" (To be) also works as a linking verb but indicates temporary states:

- Eu estou cansado

I am tired - O café está frio

The coffee is cold

Transitive verbs need an object to complete their meaning.

Most action verbs fall into this category:

- Eu compro pão

I buy bread - Ela lê jornais

She reads newspapers

Some verbs can work both ways depending on context, but the SVO pattern holds strong when you've got a transitive verb with its object.

Where adverbs fit in

Adverbs modify verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs. They usually come right after the verb they're modifying:

- Ele fala rapidamente

He speaks quickly - Nós comemos bem

We eat well - Ela canta lindamente

She sings beautifully

Sometimes adverbs appear at the beginning of the sentence for emphasis:

- Sempre acordo cedo

I always wake up early - Hoje vou ao mercado

Today I'm going to the market

The flexibility with adverb placement gives you some room to adjust your sentence structure based on what you want to emphasize, but sticking them after the verb works most of the time.

Pronouns and possessive forms

Portuguese has subject pronouns, but remember, you can drop them most of the time:

- Eu (I)

- Você (You, informal in Brazilian Portuguese)

- Ele/Ela (He/She)

- Nós (We)

- Vocês (You all)

- Eles/Elas (They)

In Brazilian Portuguese, "você" is the standard way to say "you" in casual conversation. European Portuguese uses "tu" more often for informal situations.

Possessive adjectives come before the noun:

- "Meu livro" (My book)

- "Sua casa" (Your house)

- "Nosso carro" (Our car)

These possessive forms also need to match the gender and number of the thing being possessed, not the person who owns it:

- "Minha mãe" (My mother, feminine)

- "Meus amigos" (My friends, masculine plural)

Practical sentence building examples

Let's put this all together with some everyday sentences you'd actually use:

Simple present tense:

- Eu trabalho em São Paulo

I work in São Paulo - Você gosta de café?

Do you like coffee? - Nós estudamos português

We study Portuguese

With adjectives:

- Ele tem um carro novo

He has a new car - A comida brasileira é deliciosa

Brazilian food is delicious - Minha professora é muito paciente

My teacher is very patient

Questions with interrogatives:

- Onde você mora?

Where do you live? - Que horas são?

What time is it? - Por que você estuda português?

Why do you study Portuguese?

Negative forms:

- Não entendo essa palavra

I don't understand this word - Ela não bebe álcool

She doesn't drink alcohol - Não temos tempo

We don't have time

Brazilian Portuguese versus European Portuguese

The basic sentence structure stays the same between Brazilian Portuguese and European Portuguese, but you'll notice some differences in pronoun usage and vocabulary.

Brazilian Portuguese tends to use "você" as the standard second-person pronoun, while European Portuguese uses "tu" more frequently in informal contexts. This affects verb conjugation:

- Brazilian: "Você fala português?" (You speak Portuguese?)

- European: "Tu falas português?" (You speak Portuguese?)

The verb form changes from "fala" to "falas" because "tu" takes a different conjugation pattern.

European Portuguese also tends to use object pronouns more formally and places them differently in sentences, but that's getting into more advanced territory. For basic sentence structure, the SVO pattern holds true in both variants.

Common mistakes to avoid

- Beginners often forget that adjectives need to match the noun in gender and number. Saying "a casa grande" (The big house, feminine) instead of "a casa grand" keeps your Portuguese sounding natural.

- Another common slip-up is trying to use English word order for questions. Remember, you don't need to flip anything around. "Você quer café?" works perfectly as a question with just the intonation change.

- Don't stress too much about dropping subject pronouns at first. It's totally fine to say "Eu falo português" even though native speakers might just say "Falo português." You'll naturally start dropping them as you get more comfortable.

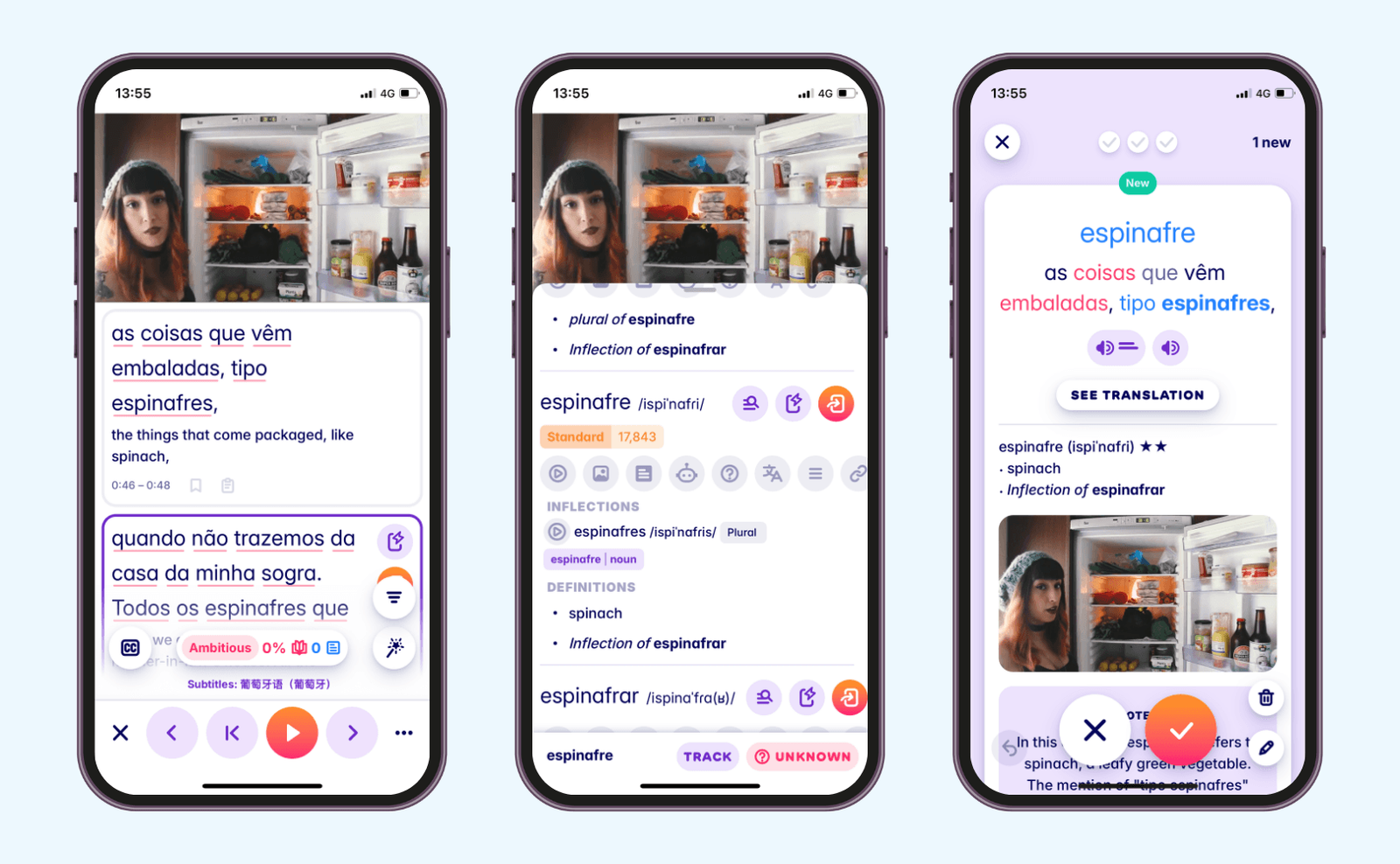

If you want to practice these sentence structures with real Portuguese content, Migaku's browser extension and app let you look up words and save sentences while watching Brazilian shows or reading articles. Makes it way easier to see how native speakers actually use these patterns. There's a 10-day free trial if you want to check it out.

You're on a fast track to learn Portuguese sentence structure as an English speaker

The Portuguese language gives you a solid foundation with its SVO structure, making it pretty accessible for English speakers. The verb conjugations take some practice, but once you've got the basic patterns down, you can start building more complex sentences by adding adjectives, adverbs, and different tenses. When you encounter a sentence you like in dramas or shows, you can also analyze its components, which can improve your understanding of grammar.

If you consume media in Portuguese, and you understand at least some of the messages and sentences within that media, you will make progress. Period.

What's your favorite Portuguese quote?