Japanese Verb Conjugation: Ultimate Guide on Japanese Conjugation With Tense

Last updated: December 29, 2025

Here's the thing about learning Japanese verbs: they're actually way more approachable than you'd think. Sure, conjugation might sound intimidating at first, but once you understand the patterns, everything clicks into place pretty quickly. Let me walk you through everything you need to know about conjugating Japanese verbs, from the basics to the practical stuff you'll actually use.

- What is Japanese verb conjugation

- The three types of verbs: Irregular, godan and ichidan

- Dictionary form and Japanese verbs stem

- Masu form (Polite form in Japanese conjugation)

- Past tense conjugation

- Te-form conjugation

- Negative Conjugation

- Potential form

- Passive form

- Volitional form

- Auxiliary verbs in conjugation

- Learning resources and practice

What is Japanese verb conjugation

Japanese verb conjugation is the system of changing verb endings to express different meanings, tenses, and levels of politeness. Every verb in Japanese can transform into multiple forms by following specific rules based on which verb group it belongs to.

The conjugation system relies heavily on the verb ending and which group the verb belongs to. Once you identify the verb group, you can predict almost every conjugation pattern for that verb.

The three types of verbs: Irregular, godan and ichidan

Every Japanese verb falls into one of three categories:

- Godan verbs

- Ichidan verbs

- Irregular verbs

This classification determines how you'll conjugate them.

Godan verbs (U-verbs)

Godan () verbs are also called u-verbs because their dictionary form always ends in one of nine possible u-vowel sounds: u, tsu, ru, ku, gu, bu, mu, nu, or su. The name godan means "five steps," referring to how these verbs move through all five Japanese vowel sounds during conjugation.

Examples of godan verbs:

- kaku () to write

- yomu () to read

- hanasu () to speak

- kau () to buy

- matsu () to wait

The key thing about godan verbs is that the final syllable changes its vowel sound depending on the conjugation. For kaku (), the "ku" part shifts to "ka," "ki," "ke," or "ko" depending on what form you need.

Ichidan verbs (Ru-verbs)

Ichidan () verbs are simpler. The name means "one step" because these verbs only use one vowel row for conjugation. These verbs always end in either -eru or -iru in their dictionary form, and you conjugate them by dropping the final ru and adding different endings.

Examples of ichidan verbs:

- taberu () to eat

- miru () to see/watch

- neru () to sleep

- okiru () to wake up

- oshieru () to teach

Here's where it gets tricky: some verbs that end in -eru or -iru are actually godan verbs, like hairu () to enter or kaeru () to return home. You'll need to memorize which group these belong to, but honestly, you pick it up naturally through exposure.

Irregular verbs

Japanese only has two truly irregular verbs: suru (する) to do and kuru () to come. That's it. Pretty manageable compared to languages like English or French with dozens of irregular verbs.

These two verbs have unique conjugation patterns that don't follow godan or ichidan rules. You just memorize their forms separately.

Dictionary form and Japanese verbs stem

The dictionary form is the base form of any Japanese verb, the version you'd find in a dictionary. It's also called the plain form or casual present affirmative tense.

For example, taberu (), kaku (), and suru (する) are all dictionary forms.

The verb stem is the part that remains after you remove the conjugating ending.

- For ichidan verbs, the stem is everything before the final ru. For taberu (), the stem is tabe.

- For godan verbs, you typically change the final u-sound to an i-sound to get the stem. For kaku (), the stem is kaki.

Understanding the stem matters because many conjugations build directly from it.

Masu form (Polite form in Japanese conjugation)

The masu (ます) form is your go-to polite form for everyday conversation. You'll use this when talking to people you don't know well, in professional settings, or when you want to sound respectful.

For ichidan verbs, drop the ru and add masu:

- taberu () becomes tabemasu ()

- miru () becomes mimasu ()

For godan verbs, change the final u-vowel to an i-vowel and add masu:

- kaku () becomes kakimasu ()

- yomu () becomes yomimasu ()

- hanasu () becomes hanashimasu ()

For irregular verbs:

- suru (する) becomes shimasu (します)

- kuru () becomes kimasu ()

The masu form itself can conjugate further for negative (masen), past tense (mashita), and negative past (masen deshita).

Past tense conjugation

Japanese has two main past tense forms: the plain past and the polite past.

Plain past tense (ta-form)

For ichidan verbs, drop ru and add ta:

- taberu () becomes tabeta ()

- miru () becomes mita ()

For godan verbs, the conjugation pattern depends on the final sound. This is where things get a bit more complex:

- Verbs ending in u, tsu, ru become tta: kau () becomes katta (), matsu () becomes matta ()

- Verbs ending in ku become ita: kaku () becomes kaita ()

- Verbs ending in gu become ida: oyogu () becomes oyoida ()

- Verbs ending in bu, mu, nu become nda: yomu () becomes yonda ()

- Verbs ending in su become shita: hanasu () becomes hanashita ()

For irregular verbs:

- suru (する) becomes shita (した)

- kuru () becomes kita ()

Polite past tense

Just add mashita to the verb stem:

- tabemashita () ate

- kakimashita () wrote

- shimashita (しました) did

Te-form conjugation

The te-form is one of the most versatile conjugations you'll learn. It connects clauses, creates continuous tenses, makes requests, and serves as the base for several other forms.

How do you conjugate a verb into te form? The pattern is almost identical to the past tense, except you use te/de instead of ta/da.

For ichidan verbs:

- taberu () becomes tabete ()

- miru () becomes mite ()

For godan verbs:

- kau () becomes katte ()

- kaku () becomes kaite ()

- oyogu () becomes oyoide ()

- yomu () becomes yonde ()

- hanasu () becomes hanashite ()

For irregular verbs:

- suru (する) becomes shite (して)

- kuru () becomes kite ()

The te-form lets you say things like "tabete kudasai" () please eat, or create the progressive tense by adding iru (いる): "tabete iru" () is eating.

Negative Conjugation

Negative forms express what someone doesn't do or didn't do.

Plain negative (nai-form)

For ichidan verbs, drop ru and add nai:

- taberu () becomes tabenai ()

For godan verbs, change the final u-vowel to an a-vowel and add nai:

- kaku () becomes kakanai ()

- yomu () becomes yomanai ()

Exception: verbs ending in u like kau () become kawanai (), not kauanai.

For irregular verbs:

- suru (する) becomes shinai (しない)

- kuru () becomes konai ()

Polite negative

Add masen to the verb stem:

- tabemasen () doesn't eat

- kakimasen () doesn't write

Negative past

The plain form is nakatta:

- tabenakatta () didn't eat

- kakanakatta () didn't write

The polite form is masen deshita:

- tabemasen deshita ()

- kakimasen deshita ()

Potential form

The potential form expresses ability or possibility, like "can do" in English.

For ichidan verbs: Drop ru and add rareru:

- taberu () becomes taberareru () can eat

- miru () becomes mirareru () can see

Many speakers use the shortened られる form, dropping the ra: tabereru, mireru. You'll hear both.

For godan verbs: Change the final u-vowel to an e-vowel and add ru:

- kaku () becomes kakeru () can write

- yomu () becomes yomeru () can read

- hanasu () becomes hanaseru () can speak

For irregular verbs:

- suru (する) becomes dekiru (できる) can do

- kuru () becomes korareru () can come

Passive form

The passive form indicates that the subject receives the action rather than performs it.

For ichidan verbs: Drop ru and add rareru:

- taberu () becomes taberareru () to be eaten

For godan verbs: Change the final u-vowel to an a-vowel and add reru:

- kaku () becomes kakareru () to be written

- yomu () becomes yomareru () to be read

For irregular verbs:

- suru (する) becomes sareru (される)

- kuru () becomes korareru ()

Volitional form

The volitional form expresses intention or suggestion, like "let's do" or "I will do."

For ichidan verbs: Drop ru and add you:

- taberu () becomes tabeyou () let's eat

- miru () becomes miyou () let's watch

For godan verbs: Change the final u-vowel to an o-vowel and add u:

- kaku () becomes kakou () let's write

- yomu () becomes yomou () let's read

- hanasu () becomes hanasou () let's speak

For irregular verbs:

- suru (する) becomes shiyou (しよう)

- kuru () becomes koyou ()

Auxiliary verbs in conjugation

Auxiliary verbs attach to main verbs to add extra meaning. The te-form often combines with auxiliary verbs to create new expressions.

Common auxiliary verbs include:

- iru (いる) after te-form creates progressive tense: tabete iru () is eating

- aru (ある) after te-form shows completed state: kaite aru () is written

- oku (おく) after te-form means doing something in advance: yonde oku () read in advance

- shimau (しまう) after te-form shows completion: tabete shimau () finish eating

These auxiliary verbs themselves conjugate normally, so you can say tabete imasu () for polite progressive or tabete ita () for past progressive.

Learning resources and practice

Want sites that break down conjugation into manageable pieces? There are some solid resources out there.

- Tae Kim's Guide to Japanese Grammar offers clear explanations of each verb form with plenty of examples. The site breaks conjugation down systematically without overwhelming you.

- JapaneseVerbConjugator.com lets you type any verb and see all its conjugations instantly. Super useful for checking your work.

- Imabi provides detailed grammatical explanations if you want to go deep into the linguistic side of things.

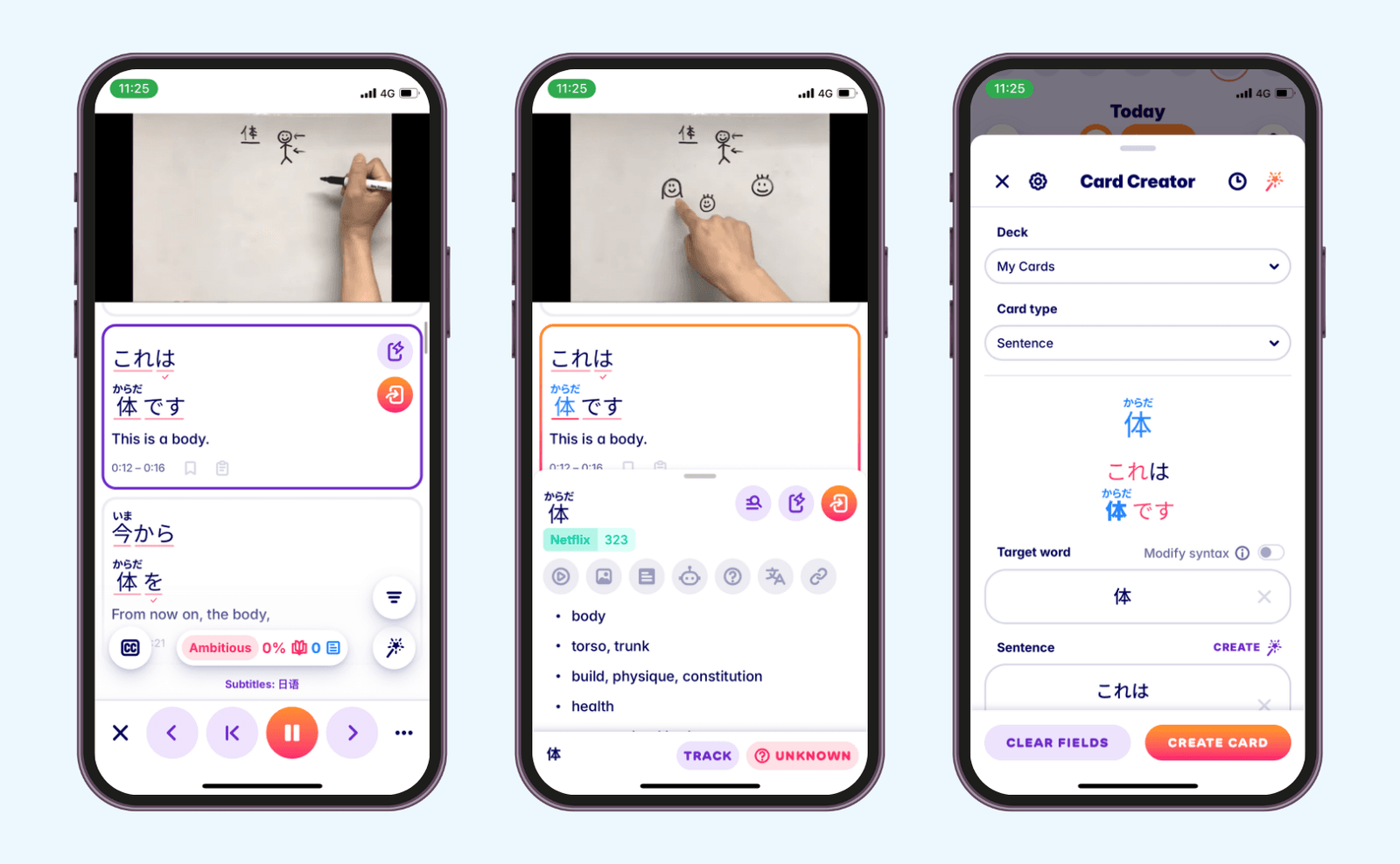

- Migaku's browser extension and app let you look up verbs instantly while watching shows or reading articles. You can see conjugations in context and save examples directly to your flashcards. There's a 10-day free trial if you want to check it out.

Conquering the common verb conjugations is worth celebration!

Master the basic patterns for dictionary form, masu form, te-form, past tense, and negative forms, and you'll have the foundation for most everyday Japanese. From there, you can build up to potential, passive, volitional, and causative forms as you progress.

The key is consistent practice with real content. Conjugation tables help you understand the patterns, but actually reading and listening to Japanese is what makes it stick.

If you consume media in Japanese, and you understand at least some of the messages and sentences within that media, you will make progress. Period.

Consistent hard work leads to success!