Classical Japanese: Introduction to Japanese Classical Bungo and Kobun Grammar

Last updated: January 26, 2026

So you've been learning modern Japanese for a while, maybe you can read manga or watch anime without subtitles, and then you pick up a classical text or try reading some old poetry and... nothing makes sense. Welcome to bungo (), the world of classical Japanese. This stuff shows up everywhere from historical literature to formal ceremonies, and honestly, if you want to read classics like The Tale of Genji or understand traditional poetry, you need at least some grasp of how classical japanese works. Let's break down what makes kobun () different and how you can start wrapping your head around it.

What is classical Japanese: Kobun and bungo

Classical Japanese refers to the forms of the Japanese language used roughly from the Heian period (794-1185) through the early modern era. People call it bungo (), which literally means "literary language," or kobun (), meaning "old writing." These terms get used pretty interchangeably, though kobun often refers specifically to the texts themselves while bungo describes the grammar system.

Here's the thing: Classical Japanese preserved grammar patterns and vocabulary that evolved differently in spoken language. By the time modern Japanese standardized in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the written classical form had become quite distant from everyday speech. Think of it like how English speakers today need special training to read Shakespeare or Chaucer, except the gap between classical and modern Japanese is even wider in some ways.

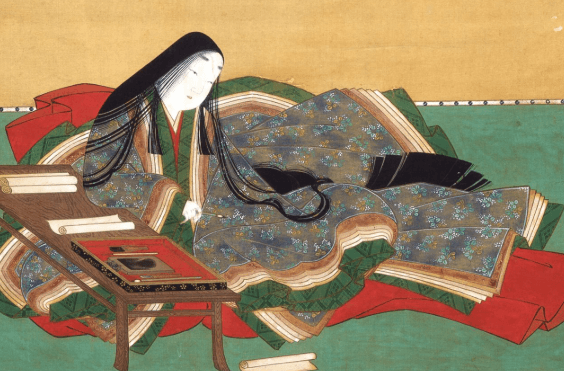

The classical Japanese you'll encounter most often comes from the Heian period, which was the peak time for Japanese court literature. Works like Genji Monogatari () or Makura no Sōshi () established many of the conventions that became standard for classical writing. Even texts written centuries later often followed these grammatical patterns because they were considered proper literary style.

Why learn classical Japanese

Japanese high school students actually study kobun as part of their curriculum, kind of like how English students read Shakespeare.

- If you want to read historical documents, classical poetry, or understand references in modern media that draw on classical literature, you need some foundation in how classical Japanese works.

- The grammar patterns show up in formal modern contexts too. Certain set phrases, ceremonial language, and even some business expressions preserve classical forms.

- Plus, understanding classical Japanese gives you insight into how the Japanese language evolved and why modern Japanese grammar works the way it does.

Grammar differences from modern Japanese

The grammar is where classical Japanese really diverges from what you're used to. Verb conjugations work differently, adjectives have alternate forms, and auxiliary verbs carry meanings that modern Japanese expresses through different structures.

Verb conjugations in classical Japanese

Classical Japanese verbs conjugate into different bases than modern Japanese verbs. While modern Japanese uses what's often called the "masu-stem" or "i-form," classical Japanese organized verb conjugation around six bases: mizenkei (), renyōkei (), shūshikei (), rentaikei (), izenkei (), and meireikei ().

Each base served specific grammatical functions. The mizenkei (Irrealis base) attached to negative auxiliaries and certain other helpers. The renyōkei (Continuative base) connected to other verbs or formed noun phrases. The shūshikei (Terminal base) ended sentences. The rentaikei (Attributive base) modified nouns. The izenkei (Realis base) worked with conditional and perfective auxiliaries. The meireikei (Imperative base) formed commands.

For example, take the verb kaku () meaning "to write":

- Mizenkei: kaka ()

- Renyōkei: kaki ()

- Shūshikei: kaku ()

- Rentaikei: kaku ()

- Izenkei: kake ()

- Meireikei: kake ()

The verb categories themselves differed slightly too. Classical Japanese had four-grade verbs (yodan ), two-grade verbs (nidan , both upper and lower), one-grade verbs (ichidan ), and irregular verbs. Modern japanese simplified many of these patterns.

Adjective forms and auxiliaries

Classical Japanese adjectives (keiyōshi ) conjugated differently from modern ones. The terminal form often ended in -shi (し) rather than the modern -i (い). So "beautiful" would be utsukushi () in terminal form, compared to utsukushii () in modern japanese.

Adjective conjugation followed its own base system, and certain forms that merged in modern Japanese stayed distinct in classical Japanese. The attributive and terminal forms sometimes differed, which modern Japanese largely lost.

The auxiliary verb system is probably the trickiest part of classical japanese grammar. Auxiliaries like nari (なり), tari (たり), ki (き), keri (けり), and many others attached to verb bases to express tense, aspect, mood, and evidentiality in ways that modern Japanese handles differently.

Take nari (なり) for example. How does nari work? This auxiliary had multiple functions depending on context. One nari served as a copula (like modern da/desu), attaching to nouns and the rentaikei of adjectives. Another nari indicated completion or state, attaching to the mizenkei of verbs. You had to distinguish them by what they attached to and the overall sentence meaning.

The auxiliary ki (き) marked past tense with direct experience, while keri (けり) indicated past events the speaker learned about indirectly or realized. Modern japanese lost this evidential distinction, mostly using -ta (た) for all past tense regardless of how you know about it.

Particles and grammar patterns

Many particles worked the same in classical Japanese as they do now, but some had different functions or additional uses. The particle wo (を/ヲ) could mark locations of movement, overlapping with modern wo and o usage. The particle ni (に) had similar but slightly broader functions.

Some particles that exist in modern Japanese had different connotations. Others fell out of common use entirely. The possessive/nominative particle no (の) worked similarly, but classical Japanese used it in some constructions that modern Japanese handles differently.

Question particles differed too. Classical Japanese used ya (や), ka (か), and others in patterns that don't map one-to-one with modern usage.

Historical kana usage and orthography

When did this w- get attached to the beginning of kana word in old form? The historical kana orthography (, rekishiteki kanazukai) preserved older pronunciations that had changed by the time kana standardized. Many sounds that merged in modern Japanese stayed distinct in classical spelling.

For instance, the particles wa (は), wo (を), and e (へ) are written with ha, wo, and he in modern Japanese even though they're pronounced differently. That's a remnant of historical kana. Classical Japanese had even more of these distinctions.

The kana system itself included characters that modern Japanese dropped. The syllabary had wi (ゐ/ヰ) and we (ゑ/ヱ), which merged with i and e sounds. Historical texts also distinguished between different o sounds and other vowels that modern Japanese no longer separates.

Reading classical Japanese texts means getting comfortable with historical kana usage. Most modern editions of classical texts include annotations or convert to modern kana, but if you're reading original manuscripts or want a deeper understanding, you need to recognize these patterns.

The w- consonant specifically appeared in more positions historically. Words that now start with vowels often had w- in classical pronunciation, like wotoko (をとこ) for "man," now otoko. The w- gradually dropped from most positions except word-initial before 'a' sound.

Honorific language and vocabulary

Classical Japanese had elaborate honorific systems that make modern Japanese keigo look simple. Different verb forms, special vocabulary, and complex grammatical patterns expressed social hierarchy and respect.

Honorific verbs like tamau () and humble forms like haberu () appeared constantly in court literature. The choice of honorific level indicated relationships between characters and the narrator's perspective toward them.

Vocabulary differs substantially between classical and modern Japanese. Many common classical words fell out of use or changed meaning. A classical Japanese dictionary becomes essential for reading, since you can't always guess meanings from modern Japanese knowledge or even from kanji alone.

Some classical vocabulary survived in set phrases or formal contexts. Other words evolved into modern terms with shifted meanings. Reading classical texts means building a separate vocabulary base alongside your modern Japanese.

Reading classical Japanese texts

So how do you actually start reading kobun?

- Most learners begin with annotated editions of classical texts that provide modern Japanese translations, grammar notes, and vocabulary help. Textbooks designed for Japanese high school students work great for this, since they assume you can read Japanese but need classical grammar explained.

- Start with simpler texts before jumping into complex literature. Collections of classical poetry or short prose pieces let you practice grammar patterns without getting overwhelmed. Gradually work up to longer narratives as you get comfortable with common constructions.

- Translation practice helps solidify your understanding. Try translating short passages into modern Japanese or English, then check your work against published translations. You'll quickly see where you misunderstood grammar or missed nuances.

- Resources for learning classical Japanese have expanded in recent years. Textbooks, online guides, and reference materials make it more accessible than ever. A good classical Japanese grammar reference and dictionary are your essential tools.

- Join study groups or find other learners to discuss confusing passages with. Classical japanese can be ambiguous, and sometimes you need multiple perspectives to figure out what's going on in a sentence.

Anyway, if you're serious about diving into classical Japanese texts, having good lookup tools makes a huge difference. Migaku's browser extension works with Japanese content and lets you save vocabulary as you encounter it, which helps when you're building that separate classical vocabulary base. There's a 10-day free trial if you want to see how it handles looking up classical terms and kanji.

FAQs

Start your kobun reading journey with a dictionary

There are online kobun and classical Japanese dictionaries to guide you in your kobun reading journey. At first, you might take half an hour to read through a paragraph, but as you get more and more familiar with the classical grammar rules, you can understand the texts instantly. As English speakers, we all struggle to read Shakespeare at the start!

If you consume media in Japanese, and you understand at least some of the messages and sentences within that media, you will make progress. Period.

Translation usually fails to convey the layers of meanings in classical works.